In September of 1892 Orville started grammar school at University Park in Denver. Orville’s father was a member of the school board and “there were just a few pupils so they finally found a building they could use for the school---so they fixed up a bunch of long benches with flat boards for tables. The teacher of course had her home with the same residence. All books at first were for first and second graders. We attended here until the big two-story brick school was built in 1893.” O.G.B.

In 1893, one year after his wife’s death, John S. Babcock lived up to Eva’s wishes that their sons receive a good education. John Babcock, a town trustee, and legislator (not verified by author) owned several acres in University Park. He donated a portion of his farmland, in addition to money, so that the school could be constructed. The school was built in 1893 to serve the children of the University of Denver’s faculty and staff. The original building was a red brick structure that contained four classrooms and a lunchroom. University Park Elementary School was referred to as “the little red brick schoolhouse” by neighboring residents. John Babcock served as the school benefactor more than fifteen years.

“Each of the four rooms had a stove for heat and the coal heaters were surrounded by children warming their feet, drying out their stockings and attending the stoves during the winter months. Each year more and more people came. The teachers were all women. The school had two sets of turning poles and swings to play with during recess. Later, standard school seats and desks were installed. A good basement was also finished for bad weather and play. All the children during winter months would play fox and geese or tag the other party. Sometimes we would walk down to the pond and skate over the ice. The boys would have a fire ready. Teachers also skated with the pupils. Snow scenes were very common.” O.G.B

That was the beginning of Orville’s first schooling.

A year after Eva died, there was a devastating blow to many miner’s prospects, including John’s, with the Silver Depression.

Orville had chores to do as well on the property; daily orders to milk the cows on their farm. “I went after them every day, and one day I was, for some unknown reason—I didn’t go to school that morning. I left to go but I didn’t get there, and I was out in the weeds somewhere there and doing something. Well, they called me, and I didn’t answer. Finally, later on I decided I better go, so I did, and I got a good licking—I don’t know if I got a whipping or not. I got one of those about every day.” O.G.B.

Orville was often sidetracked with frogs, snakes, and toads in the numerous streams along the way. He recalled that one time he was kicked in the face by a cow while bringing the cow home.

“One evening I had gone down after the cattle. Well, I didn’t come home, so finally my father decided to go down there and see what’s the matter and he took a long buggy whip along with him. When he got down there was a little stream of water down there running slow, and I was interested in that creek as I was busy with insects and other life in the creek and in the mud. I was head over heels in there and at first, I didn’t notice him. I didn’t see him, but he come down there and stood behind me. I don’t know how long he watched me, but he watched me for quite a while. Then finally, he just kind of reached the buggy whip, kind of eased it over the top of my head. Then I came to life pretty quick. That’s one time he didn’t whip me. This was the beginning of my zoology!” O.G.B.

During Orville’s boyhood days his father obtained a pair of peafowls in full plumage and “that male did a lot of strutting before the hen. At times the two of them would fly away to a nearby nursery and hide. They were hard to find because their coloration blended in with the surroundings. When Orville would find them, he’d carry each one home. There was a small 3-foot roof overhang by his bedroom window. At about 5 am in the summer, the peafowl would give their morning call, CA-! Ca-! Ca-! Ca-! and then they would fly down.” O.G.B.

Orville began to appreciate music as a child as well. “Our neighbors, close neighbors, were Germans and they were very musical. I heard a group of three or four musicians playing together on string instruments. I kind of fell for it. I wanted a mandolin especially or a guitar and finally my father said yes, so I got a violin. Then I took lessons on that. I took six or eight lessons and then, later on, I was so interested when I was playing together with stringed instruments, that I bought a mandolin and studied for a year on my mandolin, practicing four hours a day, every day. That’s really what I did! In the meantime, I got in with a man who had a credit instrument orchestra, so I played in there. Course I wasn’t the top player, but I played anyhow, the second mandolin. Played that off and on while I was going to the grammar school and to the preparatory school at the University of Denver.” O.G.B.

He remembers his school friend Maynard Trot. “We used to go out walking every weekend. We’d almost always go walk and sing some of our grammar school tunes. We always walked for pleasure but always collected anything we were interested in. Often times we’d collect anything we could, rocks, wood, or anything else, returning home from the prairies. Sometimes we found the walks a couple of miles away. We also found many of the lizards but rarely found the skinks.”

Orville received a certificate of promotion from sixth to seventh grade as follows: Orthography 75, Reading 89, Arithmetic 75, Geography 75, Grammar 70, composition 80, General Work 84, U.S. History 75, Physiology 88, Penmanship 85, Nature Study 99, drawing 93 - Signed Mabel L. Daniels, Teacher, June 9th, 1899.

He received a certificate of promotion from seventh to eighth grade the next year. Orthography 70, Reading 80, Arithmetic 80, Geography 80, Grammar 85, Composition 82, History 82, Physiology 84, Penmanship 82 - Signed Mabel L. Daniels, Teacher, June 15th, 1900.

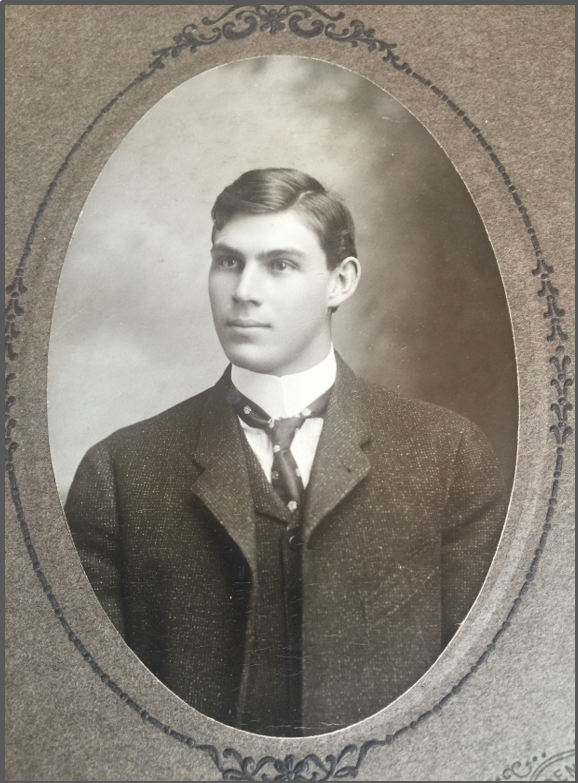

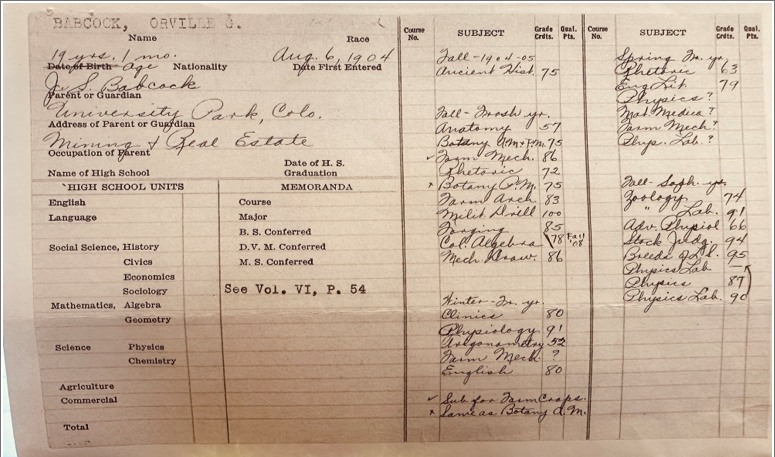

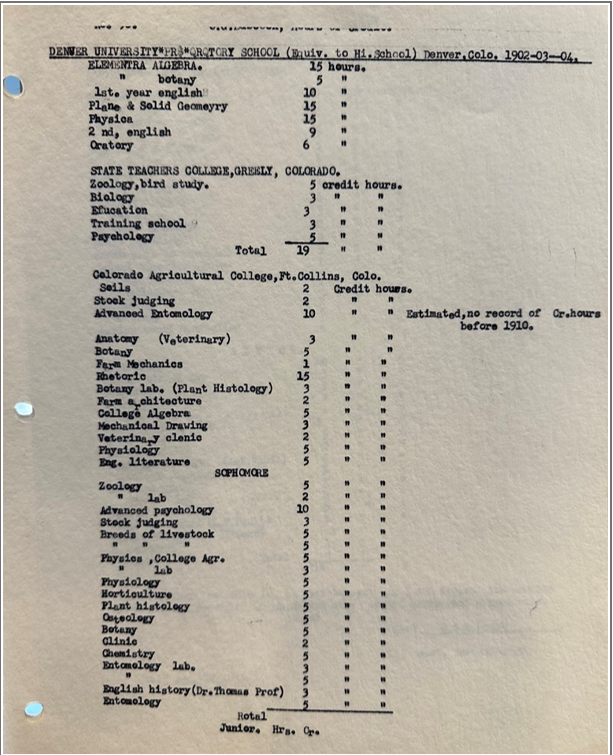

Orville continued his studies, first attending business college at Wallace Business College, in the heart of Denver from September 1902 to June 1903. The next two years, from 1902-1904, he succeeded and was admitted the University of Denver Preparatory School in University Park. His scores were: Algebra 86, English 85, Geometry 60, Algebra 90, Oratory pass Algebra 91, Biology 85, Oratory pass, Physical Culture pass, Chemistry fair, English 90, Mathematics 2-89, Physics 75 g, Methodist institution. Here he studied physics, chemistry, algebra, geometry, English literature, writing and botany.

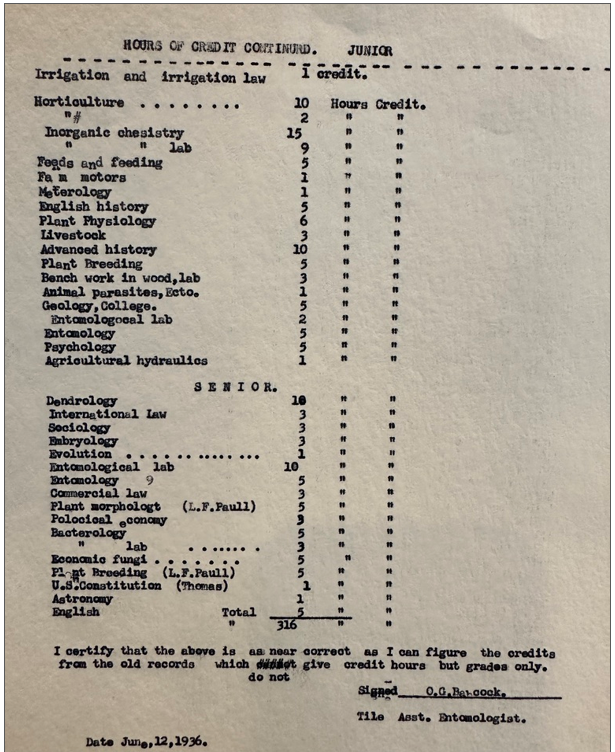

In 1936 Orville typed up this document, a two-page summary reflecting his coursework and associated hours of credit reflecting his education at Denver University Preparatory School.

Professor Cutler was a zoologist and was Orville’s botany instructor and a good one as he recalls. “So, I took a three-month course in botany. My father couldn’t understand all that, why I was doing all that. I had my room chock full of plants and flowers. So, I guess I was a naturalist. I remember we had to collect and classify twenty-five flowers (botanical names) as a final test. Laboratory exercises were always taken along with the subject studies.”

“And then I studied chemistry—high school chemistry. I always enjoyed that, every bit of it and then of course physics. I used to read that book on physics—while I was riding downtown in a streetcar.”

“And then mathematics, I enjoyed that, had no trouble with it at all, and I remember not only physics but also geometry. And the professor’s daughter was also studying geometry, and we went through plain and solid geometry in one year, and I feel kind of honored to say that his daughter and myself were the only two that got out of the final examination.”

“We had a good instructor; fine instructor and he had lots of patience. That made me think of a little joke we had on him. We, two or three of us together, planned it up. So, while he was working on this, he was teaching the geometry, and every one of them wanted to raise a hand and wanted to know how to work such and such a problem. So, they gave it out to him, and they are right angles, …and it kind of slipped by him at first, but each of the triangles had the same length, so he suddenly got the point, and that answer would be zero. But he took it good natured.”

“Some of the classes became pretty rough in school. Eighty-year-old Dr. Hide, Instructor in Latin and Sanskrit and religion, got a black eye as a result of interfering with one of the class sisters.”

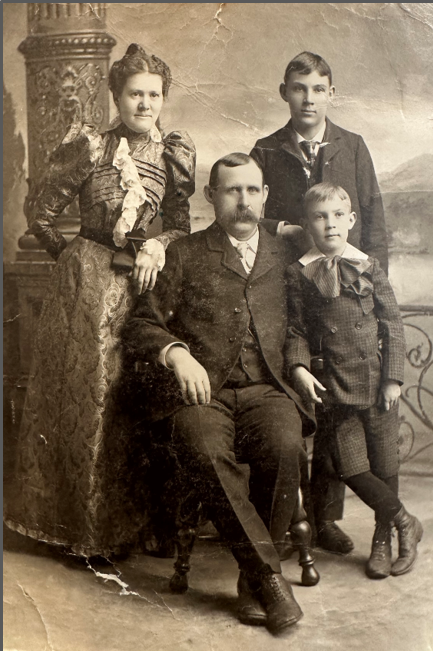

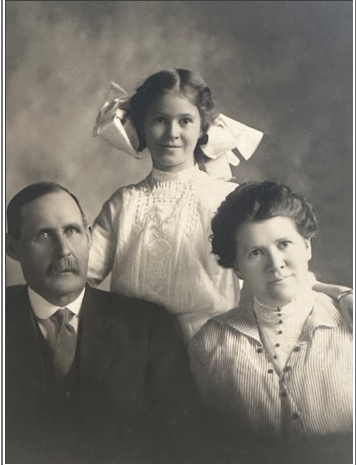

Katherine Babcock with her parents, John and Maggie

All the study did not mean there was no socializing. Orville recalls a special party. “The parents of one of the girls in our class gave an evening to the class at their residence on the outer part of the city. The party was getting along nicely, and all were having a fine time when all of a sudden, a jealous higher class appeared on the scene to break up the party. They did but the men tied up all the interfering men and held them there until all of the girls and a few men reached the last streetcar and held it there until all of our side reached the streetcar and got away before the crowd could catch us. The streetcar was the last midnight car. Our party returned home in time to join the classes, with no loss except sleep.”

Orville’s sister, Katherine, was born in 1904. “She was graduated from grammar school of 8th grade, entered South Denver High school, graduated, and then took business courses. She went on to be an assistant in the clerical department of the Denver school until retirement.”

At one-point John became a custodian in the school where he had donated land for the building site and most likely helped with the construction of the school. After Maggie died in 1937, John Steel moved into a home with his daughter, Katherine. This may have been a rental home they owned when living in the large house. It was located just around the corner.

Always an affectionate child, Katherine loved and cared for her father throughout his life until his death in 1947 at the age of ninety-six.

Orville also worked as a janitor of the school building to help pay his tuition and fees while attending the Denver University Preparatory School (1902–1904).

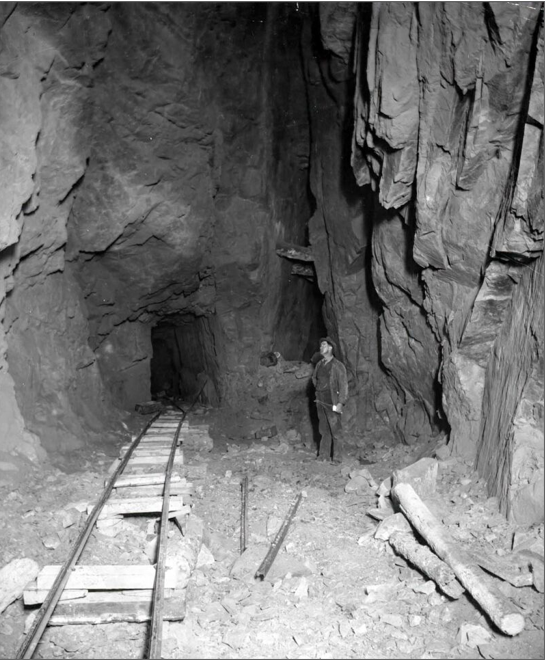

The extra money his father, John, made from mining became invested in gold mines and stock but as Orville said, “That $20,000 didn’t last.” Over time his father lost it all. That’s when we went broke in about 1906 or 07. It was then that he found a man who could be “grub staked” i.e. given food and money to do mine work and do prospect mining for himself. He did find one lead in the upper Hamlin gulch. Later he developed and then prospected still higher up in the mountains and a little west of Black hawk and Central City. This did show a small vein of lead ore Orville worked 2 or 3 summers there. The work was all hand drilling and considerable rock was removed from the tunnel. There were no promising prospects of mineral, Lead or Zinc (Lead Sulfite) of any value.

One experience he had was when a blast was set off at the inner end of the tunnel. “The fuses and powder were set and ignited. We got out right away, stood against the side wall out of the line of the tunnel. Wham! Here came a rock about 8 inches thick like a cannon ball. It hit beyond the end of the dump. Any old silver mine that had been worked was played out and all the abandoned muck piled up 50 or more feet in the dump slopes.” This was where he learned a lot about dynamite and blasting but as he writes, “in the meantime much of my time was spent collecting flowers.” In addition, his fascination with exploring insects and vertebrates continued.

“At one point when father and I was mining for lead and zinc my father and I discovered a tunnel in solid granite, it extended inward from the creek bed. Over the course of time the tunnel was basically sealed by mud and dirt. Boy, like I had to enter the tunnel. Water depth was about 8 to 10 inches. In the water flowed some salamanders, good size, 8 to 12 inches long. These mud puppies had gills. They were easily captured. Not being prepared, the salamanders were left to live in their wet retreat. This was at Hamlin Gulch, CO approximately one mile off the road near the log cabin headquarters.”

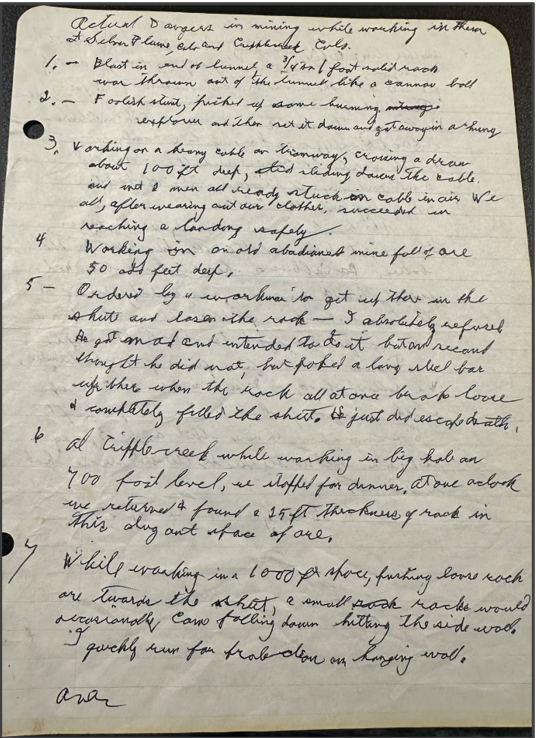

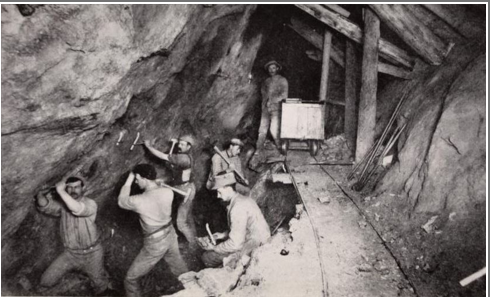

The following is transcribed from two pages written by O.G.B. about the dangers of mining he experienced while working at Silver Plume, Colorado and Cripple Creek, Colorado.

- Blast in end of tunnel a ¾ inch/1-foot solid rock was thrown out of tunnel like a cannon ball.

- Foolish stunt, picked up some burning, explored and then set it down and got away in a hurry.

- Working on a heavy cable on tramway, crossing a draw about 100 feet deep, sliding down the cable and met two men already stuck in cable in air, all wearing out our clothes, succeeded in reaching a landing safely.

- Working in an old abandoned mine full of ore fifty odd feet deep.

- Ordered by a workman to get up there in the chute and loosen the rock. I absolutely refused. He got mad and intended to do it but at second thought he did not but poked a long steel bar in there when the rock all at once broke loose and completely filled the shoot. He just did escape death.

- At Cripple Creek while working in big hole at 700-foot level, we stopped for dinner. At one o’clock we returned and found a 25-foot thickness of rock in this dug out space of ore. *

- While working in a 1000-foot space flushing loose rock ore toward the sheet, small rocks would occasionally come falling down hitting the side wall. I quickly run for broke on hanging wall.

- Another time while working in slope, a rock about twice the size of my head suddenly fell and hit the loose rock within eight to ten feet of me. To the chute I run.

- While going to work in a mine at Silver Plume, a bucket, empty, was hanging by a cable, still over the shaft. Two bosses got inside the bucket and two men and myself stood on edge of bucket and holding onto cable. The bucket was lowered, we three got on the 200 ft level and the other two went to bottom. One cable was hooked to a bucket full of bad zinc ore, signaled up, stopped at the top and broke and fell on the wooden base but not quite enough to break through. Down came a few pieces of broken lumber. We hollered back, deciding to come up the emergency ladder on side of shaft. Examination showed that only three freshly broken wires held all the weight. All other strands had rusted out. A terribly narrow escape.

*Orville commented further about this incident in a recorded interview: “But while working in this stove one day, a rock about twice the size of my head come down from a 700-foot level and hit within ten feet of me. Incidentally, later some miners were working at this same mine at the bottom. At the bottom several miners were excavating the old ore, and I didn’t happen to be in there at the time but was working beside it. Well Grainer and I after having dinner, we went back to go to work, and we found that this hole where we had been working. There was a hole about 20 foot deep and it was all filled with rock when we returned.”

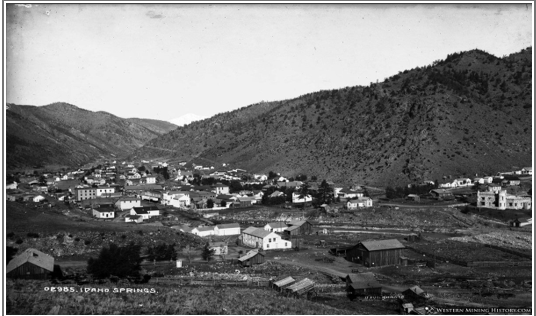

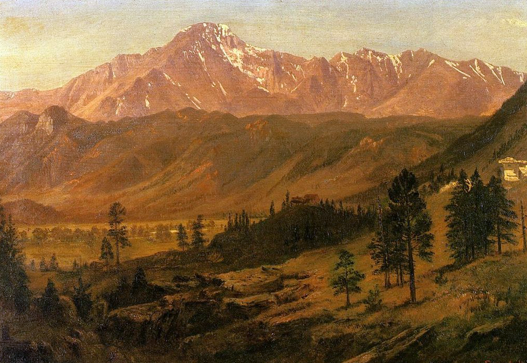

Idaho, Springs, Colorado (1890)

In the summers of 1900 to 1902 Orville worked lead mining in his father’s prospect mine up Hamlin Gulch on Fall River, located a few miles northwest of Idaho Springs.

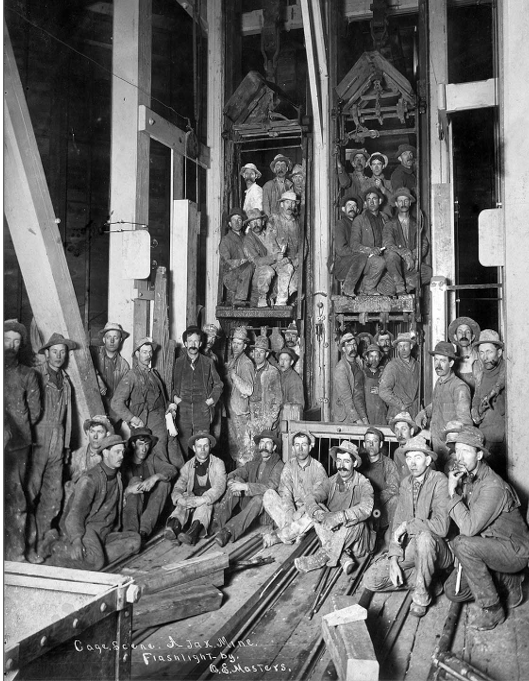

In the summer of 1903 Orville worked as a miner at the Ajax Mine located just north of Victor (one of the district’s top gold producers), in Cripple Creek, Colorado. His jobs included mucking, drilling or mining the holes to be blasted for gold. “In these mines of Colorado at Cripple Creek the shafts were mostly always vertical so some of us slept slanting a little. They were probably 1500 feet in depth. The miner was lowered down by strapping to the shafts, then hauled out to go to the surface to go to the creek with the ore.” (O.G.B.) The miners dropped 1,000 feet in 27 seconds with six to twelve men in a cage.

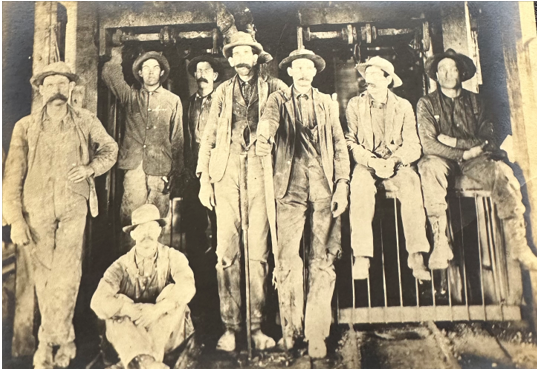

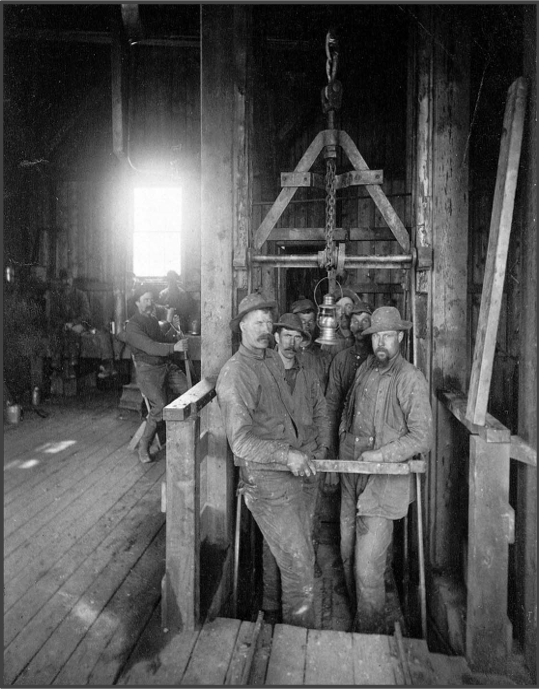

Ajax Gold Mine, Victor, Colorado (1907)

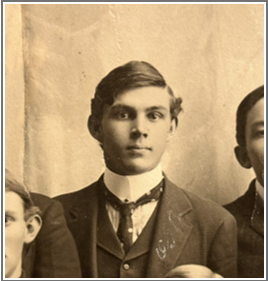

Orville is pictured above, standing second from left, holding the central rod. The last man on right is a school of mines student. The mine shaft is 1200 feet deep.

Single jacking drilling involved a lightweight hammer, usually four pounds or less. The hammer was used for hand drilling holes in rock, hammer in one hand and drill in the other.

Alternate mode of transportation

Orville’s notes and reflections:

“Arriving in Victor, Colorado soon after noon we found a one-room cabin to live in near a railroad track. The next day we started out visiting a big boss at every mine and asked for a job. Finally, the boss at the Ajax mine, accepted me and my roommate. In the meantime, a carriage of five to six men was hauled to the surface and all of the men were dead. The cause? A cave in.”

“There were 20 miles of underground workings; shafts, tunnels, cut off’s etc. in that mine.”

“Water was 10 cents a bucket. One morning while going to work, a “drunk” was sliding down drunk on the Railroad tracks. He awoke and slid further down as I passed by. “

“That evening being Sunday, my pardner and I took a walk downtown. Of course, the first thing we saw was a couple or more miners at a table gambling. The silver dollars were piled pretty high. Each player had his revolver handy. We decided we had seen enough so we moved on.”

“At the close of the season, we went to see the boss to inform him of our intention to quit because we were wishing to return to college. We had on our hobnail shoes (regular heavy work shoes and on the bottom of the entire shoe, there’s a special nail that’s quite broad after wearing it, and they put that all over the sole, because you are walking all the time on rock and gravel on the ground) and ate dinner and finished packing, two bags, grub and a compass to lead us to the top of Pike’s peak. While walking, twice we found ourselves walking right back to Victor.”

“Finally, we arrived at the base of the peak and began climbing. About midnight, we found ourselves somewhere on the side of the peak. We made camp there by a sheltered rock where we fell asleep. Awakening early the next morning we found ourselves about halfway to the top; didn’t see the sunrise as planned. We kept climbing and finally reached the peak about noontime.”

“Upon looking back where we came from, we discovered that we had walked between two lakes not knowing they were there.”

“While we were carrying our dinner buckets, somebody, a tourist remarked “These fellows must be miners.’ I guess we wore hobnailed shoes, cloths, and hats etc.”

“Of course, many crowded around us and began asking questions. Finally, we drifted to the north side of the precipice and sat down on the short shelf and ate our dinner.”

“Soon we pulled out for the walk down the peak following the railroad track most of the way. In places where there were much loose, slick rock, broken gravel, and shaky rock. Our steps would average 10 to 20 feet at each step. It was the gravel. You step on it, and it’d slide and the next thing you know, you’d slip 10 to 20 feet.”

“By evening we reached the bottom, walked to the depot and took the train back to Denver and the streetcar home.”

Transportation, or specifically rail transportation was an important component of the University Park neighborhood. Being quite distant from central Denver, community members needed speedy access to downtown. Early in 1885, the Denver Electric and Cable Railway Company began a series of experiments using an electric trolley developed by Professor Sidney Short of the University of Denver. In 1887 the Denver Circle Railroad extended a line into University Park. New electric street railways, also known as streetcars or trolleys, enabled Denver to grow outward into the prairies. In 1889, members of the Denver Tramway Company incorporated the South Denver Cable Railway Company in order to extend the Tramway's Broadway cable line through South Denver. With the extension of the Denver Tramway Company’s trolley car line south along Pearl Street from Alameda to Evans and east to the University of Denver, the surrounding neighborhoods, including University Park, began to boom.

Pike’s Peak, elevation 14,110 ft