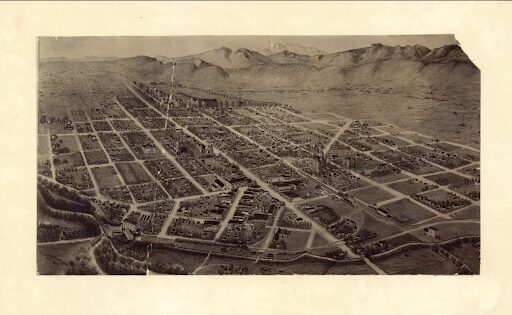

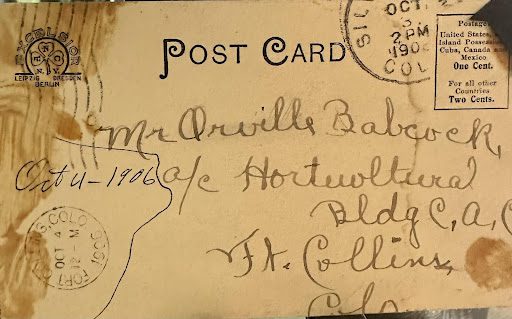

Meanwhile after spending two years in the University Preparatory School in Denver, Orville decided to go to college. He enrolled at Colorado Agricultural and Mechanical Arts College at Ft. Collins. His initial plan was to be a farmer, as his father had done. Orville turned nineteen years old one month before the start of school. He worked in the mines to earn money for college. Here, he would learn how to raise wheat. He attended college from 1904 to 1910.

It was while at college that Orville met Edith Stella Knoll, also of pioneer heritage. She was one year behind Orville in her studies.

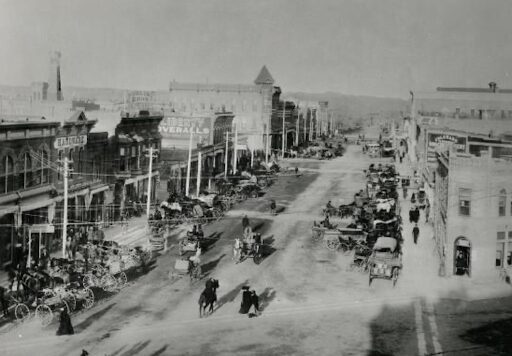

“Well, that first summer, 1904, there I worked out on a thousand-acre farm just cultivating sugar beets. That’s all I had to do. Just walk and look straight ahead for half a mile-long rows behind the cultivator. So, when summer was over with, then I come to town and instead of looking for a job, I was looking for a place to stay. I remember seeing eight or ten laborers lined up on a bench looking for work.”

“I finally got into college as an irregular (part-time) student, but then was able to get in as a regular (full-time) student. I decided I wanted to graduate, and so I registered and got a place to stay. I believe I got a job as a janitor to begin with. I held that job for about three or four years in college. Then I worked some at a restaurant downtown, but then every summer I’d go to the mines. Working there I could make more money than I could ever make on a farm. That’s why I did the mining and, my father being a miner, I’d already been to his mine, and I wanted to go back. I made four dollars a day there. That was big money.” O.G.B.

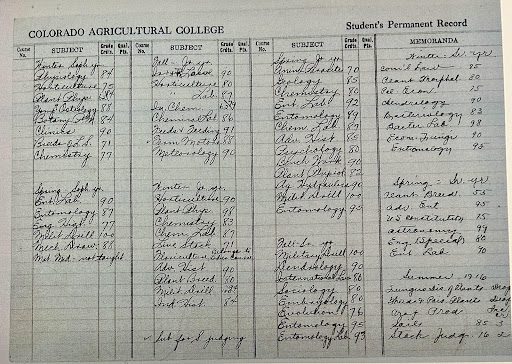

Orville told his father he was going to learn how to raise oats and wheat, but the first subject he took was veterinary science followed by courses in English, history, horticulture, entomology, and genetics. Additional courses taken included drawing, carpentry, and farm machinery. “They thought they were going to make a veterinarian out of me. So, I studied the anatomy of a horse-from one end to the other. Dissected every muscle in the animal. They put it to you on that!” O.G.B.

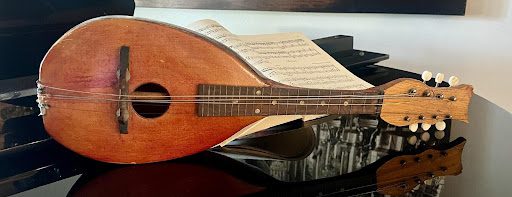

Orville took his mandolin along with him to college, but he had little time to play. Orville recalled one interesting incident while he was staying at a Scottish man’s family home. “I only stayed out in the barn. I was playing some Scotch music and a bunch of Scotch songs. Finally, I began to hear somebody singing, and there was this old Scotch fellow living next door, he and his family. He knew those songs, and he come over to where I was and came in there. I played old Scotch songs, and he knew ‘em all by heart. He really did some singing.” O.G.B.

After graduating from college Orville dropped all music. He was too busy making a living and thinking about the future. But years later he would pick it up again when his family moved to Sonora.

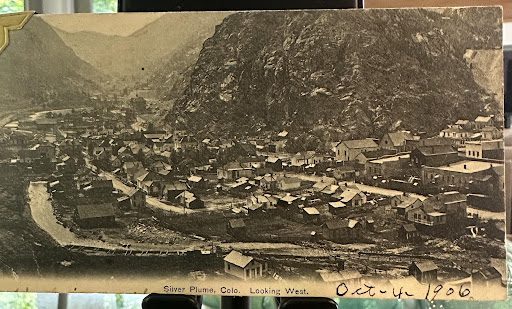

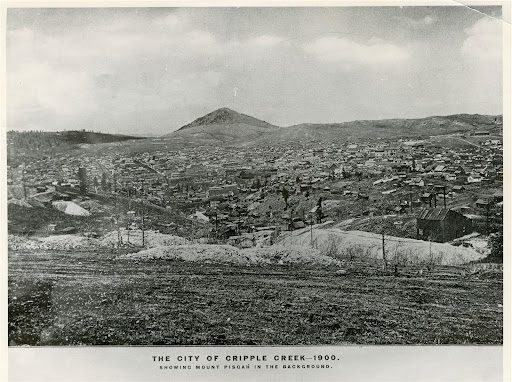

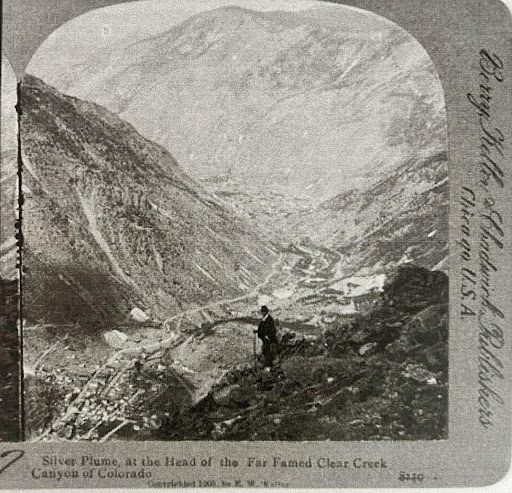

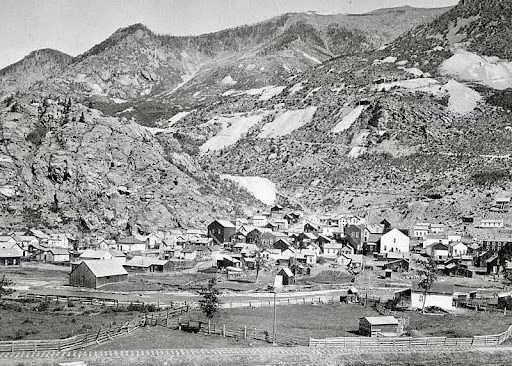

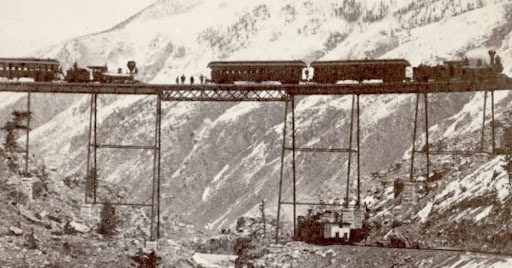

During the summer of 1904 Orville worked as a laborer on a 1,000-acre farm east of Ft. Collins. From 1905 and 1906 he continued work in the mines during the summer; gold, silver, lead, and zinc mining, concentrating with mill work at Silver Plume, Colorado and Cripple Creek, Colorado. In the evenings, Orville often played his mandolin for dancing after a day’s work.

“That evening I found my bed was in a small room. The mattress was very thick with feathers. The comforter and feather pillows was super good. The bed was warm but somewhat smothering. Such bedding I was not accustomed to.”

“This was about 1906 while mining in my father’s prospect mine when I took occasion to visit another prospector a few miles away. He lived in a log cabin, raised native hay, and had milk cows and some grain while still prospecting.”

“Father’s mine, one of them, was located several miles above Idaho Springs, and up Hamlin Gulch to a farm and residence. A dry gulch a mile further up to the north of father’s cabin. It was a one room cabin with a stove, a few cooking utensils, and a bed with one by ten lumber.”

“The old prospector was a very fine Frenchman. He had two girls, other relatives not known. His only bad habit was that he loved his wine a little too much. Ever so often he would go to Central City, get a good drunk and return home with his Topsie (horse) at about three in the morning. He always lost his way and came home hollering, “Come Topsie, Topsie. Come Topsie,” only to find his horse had returned home long before he did.”

According to stories told to Kenneth, years later: “He earned a few extra dollars by playing his mandolin for the Irish miners in nearby Georgetown. He even demonstrated to me how he learned to “jig” like the Irishmen.”

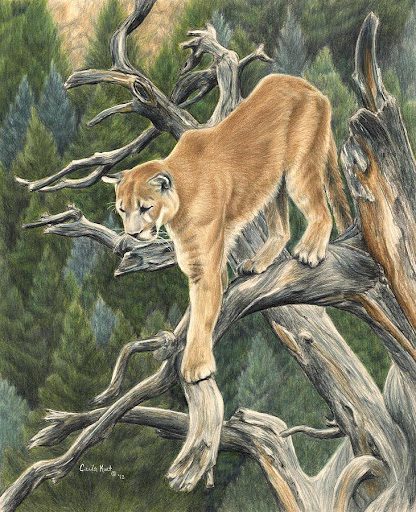

Orville continued with his reflections of this time in his life stating the following: “A mile south to Hamlin Gulch the small community would get me to bring my mandolin along to the dance. Here I played until midnight. On the way home one night, it was very dark, and I was walking alone. I walked right into a cow lying down in the middle of the road. A snort from bossy. This was not enough. Not far from the log cabin a young Mountain Lion sprung for my throat. I threw myself backwards and the young lion missed me by inches. I walked on. I walked, half run, to the cabin!”

Kenneth remembers his father recounting the story: “In order for him to play for the Georgetown miners it was necessary for him to walk from Silver Plume, down the mountain to Georgetown, several miles in the forest. One night he was attacked by a mountain lion. The lion jumped Daddy as he walked down the trail, taking a swipe at him in the dark, then ran off!”

While working at Silver Plume Mine in 1909, Orville recalled the following:

“On Sundays I usually spent my time walking by myself. Walked all over the side of the mountain which was literally pitted by prospect holes and extensive lead and zinc sand silver mines. Collected many mineral specimens. Entered many tunnels, some were dangerous due to shafts being filled with water and covered with a scum of dust upon the surface of the water. In one case, a good size stream of water was running swiftly down from the top of the tunnel, probably a quarter-second feet of water running.”

“Many of the old timber braces were in all stages of decay. The old 7.30 mine was large, mine probably 750 feet deep and well-marked. At its peak their mine apparently worked one hundred tons of lead and zinc in a day.”

“The dump was at one time quite large. Years later, probably due to a small cloud burst and very heavy rain, this accumulating water and dump all came down the semi canyon or groove in the mountain and hit and completely covered the town and all the inhabitants with water and feet of gravel. Apparently, there were no survivors, a total loss.” O.G.B.

“At one of the mines at Silver Plume, Co. the owner were salvaging all of the filth of broken ore. This material contained lead and zinc of no value at the time, hence the stopes (a dugout tunnel or space that contains the ore being mined) were well filled with valuable material.”

“Below on the tunnel floor they started working on this discarded waste ore but kept it in storage in the mine. It was now being removed (1907-1908) to be run through the mill to be concentrated to ore.”

“As often happens, any loose rock will often hang or clutch at the loading chute. The man working at the chute gave orders to me to get up in there and loosen the rock. I quickly refused; he got mad and started to punch it loose. Down came the unstable rock. He barely escaped being caught or crushed. He quickly learned his lesson.”

“It was a common fact that many students were found working on the mines. They were studying geology and mining. Some men were married and working to get a start homesteading or to run a farm. Others were year to year workers.”

“At the time, my chum and I found out that there had been a strike. The company dismissed all employees or miners. All applicants had to be new (non-union supporters). They were not miners and had never worked in a mine before. After proof of this, we got our job about 1906 and worked all summer until it was time to return to college.” O.G.B.