In 1920 Orville and his family moved to Sonora. Years later Gertrude shared her earliest reflections of Sonora: The trip from San Angelo was made in a Model T, a short drive beside construction of the first highway to Sonora, continuing on ranch roads. Sutton County was suffering from a drought and housing shortage. Our first home was a three-room structure with no electricity or running water.

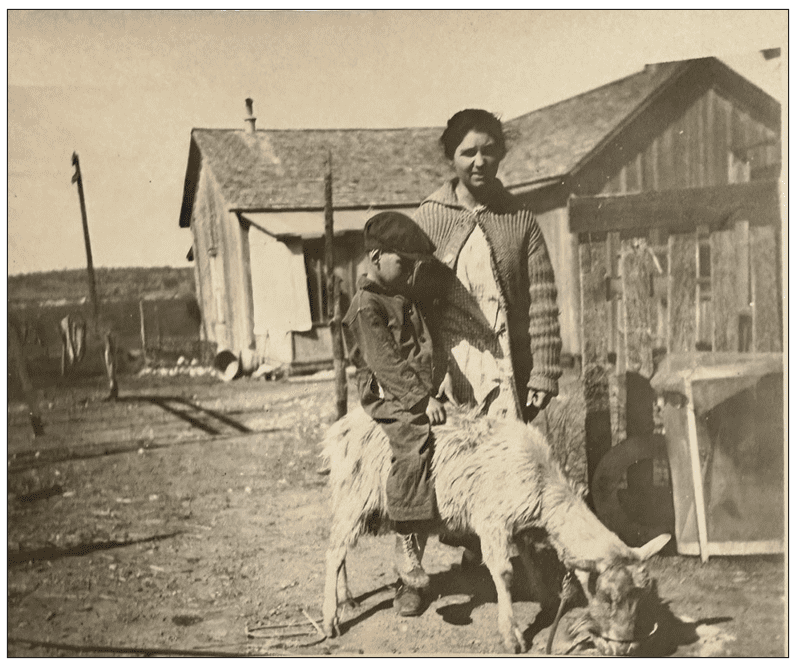

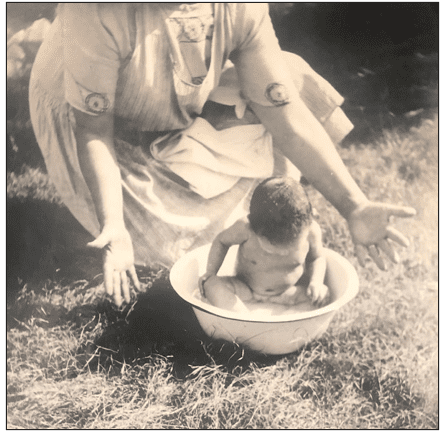

It was located on the south edge of town at 1021 South Crockett Street. There was a nice front porch, three rooms and no back porch, only a door. The house had an outdoor privy. Paper was furnished by Montgomery Ward and Sears-Roebuck Catalogues. We bathed in a #2 washtub in the kitchen, the warmest room of their three-room house. A wire fence surrounded the property and there was a wire gate in the backyard, wide enough to accommodate an automobile of the early 1920’s. There was a chicken roost in one end of the little barn in the backyard with enough room for a few goats and sheep, which Daddy occasionally brought in for observation.

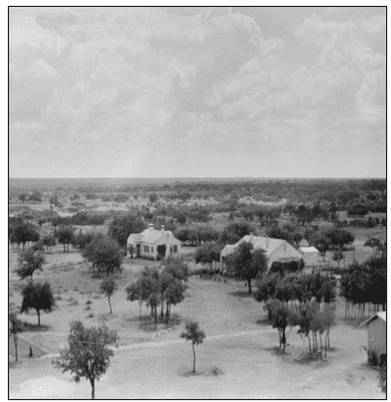

Native trees and grass were in evidence within fenced yards and little else, there being a water shortage. Frequently livestock was driven through the streets. Sonora, in 1920, numbered 1,000 persons, living in frame houses with porches. There was Pierce’s Café in the old saloon building, out of business since prohibition, but retaining its long bar and mirror. The wagon train operated by Ed Pfiester was seeing its last days.

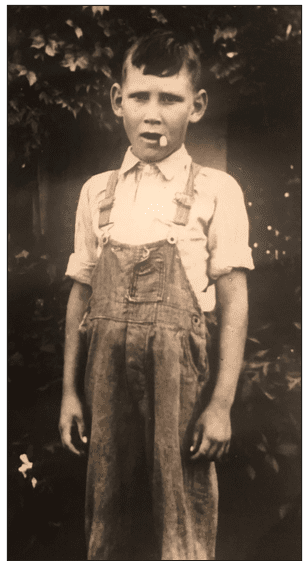

The following reflections are taken from Kenneth Babcock book, A Pilot’s Life:

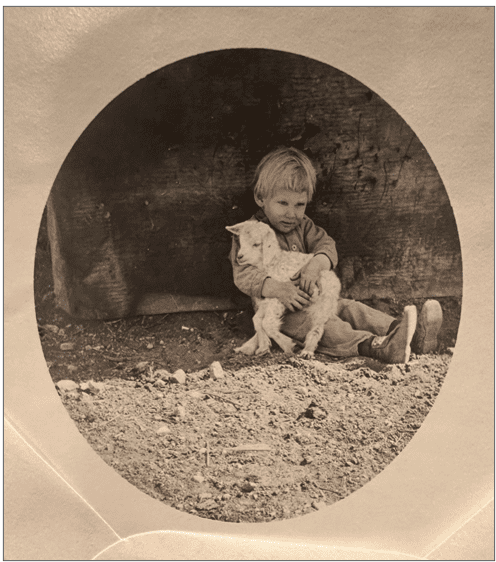

While Daddy was away at work, which was most of the time, Mother, Gertrude, and I fed the animals. We gathered the chicken eggs and kept water pails full. The goats loved to lower their heads and butt their closest target. They would chase me the minute I turned my back to them and butt me unless I turned around. They were always butting each other, or anything else that moved.

One morning, Mother bent over to pick up some clothes to hang on the line. She didn’t notice the goat behind her, and believe you me, when Mother got up off the ground, she was mad. That weekend when Daddy got home, he quickly built another pen.

In those early years of my life there were many winter nights when Mother stayed up trying to alleviate my painful earaches. She applied hot dishtowels heated above the wood stove, or rags heated in hot water. Neither did much good, but my wonderful mother tried her best. Mother would sit patiently holding her hand to my forehead and holding my hand. Her presence helped me tolerate the pain.

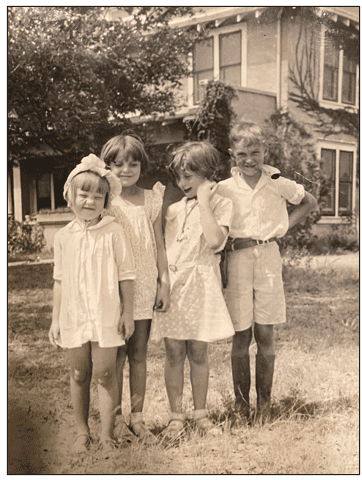

Life in the early 1920’s was much like it was during the first of the century. My sister and I were fortunate that both our parents had earned college degrees, Daddy in 1910 and Mother in 1911, so they were able to help us with our studies. However, Daddy was gone most of the time doing his research at the Texas A & M Experiment Station. Mother saw that we studied.

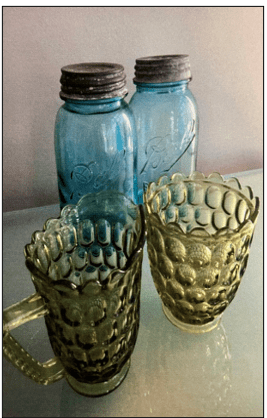

As the Experiment Station was 35 miles south of town, the government either furnished Daddy with a Model T Ford or paid him for car expenses. With roads unpaved and poorly maintained, the model T would sometimes take hours to drive those 35 miles. There were gates that had to be opened and closed, ruts in the roads to contend with, etc. It was just easier for Daddy to stay at the Experiment Station, only coming home once or twice a month, especially if it rained. Daddy being gone much of the time meant I had to be the “man of the house.” At least that’s what my mother told me. I was given the job of taking care of the chickens, the woods fires, and whatever else came up. We kept coolers on the porch that were covered with long dish towels resting in the water. The air passing through the damp towel created some evaporation which cooled the air inside. This kept food and milk cool for several days. Sonora had few paved streets in the early 1930’s, but there were electric radios, refrigerators, bigger and better automobiles, and improved phone service. A butane tank in the backyard supplied gas for stoves that replaced the wood burners. Progress during the Depression! Still, it was necessary to keep milk in sealed glazed jars to help prevent spoilage. When home delivery of ice became available, we bought an insulated wooden icebox, with a metal compartment at the top for ice. Each customer was given a cardboard sign by the ice company with the numbers 15, 25, 50, and 100 printed consecutively on the corners, signifying the pounds of ice requested. The card was put in the front window of the house and rotated so the amount of ice wanted was in the top corner. The delivery boy would chop up that amount of ice and put it in the cooler on the back porch in the icebox.

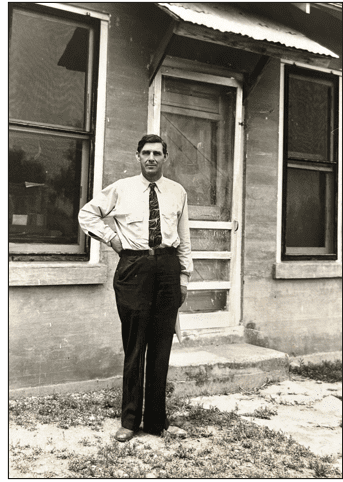

From 1941 to 1942 Orville was still in service doing work on organic chemicals. He developed the method of putting crystalized organic chemicals in solution for dipping purposes. Over 1200 formulas had been developed with only a few promising but none of them very toxic except Naphthalene which was used as a fumigant insecticide that works by turning directly from a solid into a toxic vapor. He believed the future must come through the higher hydrocarbons as plant alkaloids.

Occasionally Edith May was able to go to the Experiment Station with her daddy. This was usually during the summer when she could spend part of the week there. Two of the other scientists lived at the Station and had children about the same age as Edith May. The children had such fun playing together, especially when Edith May could join them.

More from the Kenneth Babcock’s autobiography, Life of a Pilot:

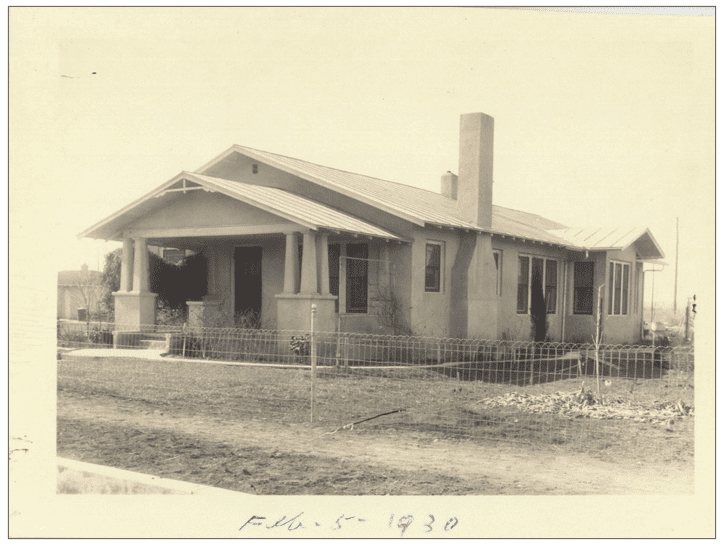

My father had been working some time on blueprints and plans for our future home. He presented the plans to purchase material, location and prices to the banker, Roy Aldwell. Agreement on the loan was reached between the two of them, and they shook hands. No papers were signed. Daddy was ready to build. Work was begun on our new baked tile home at 908 S. Crockett Street.

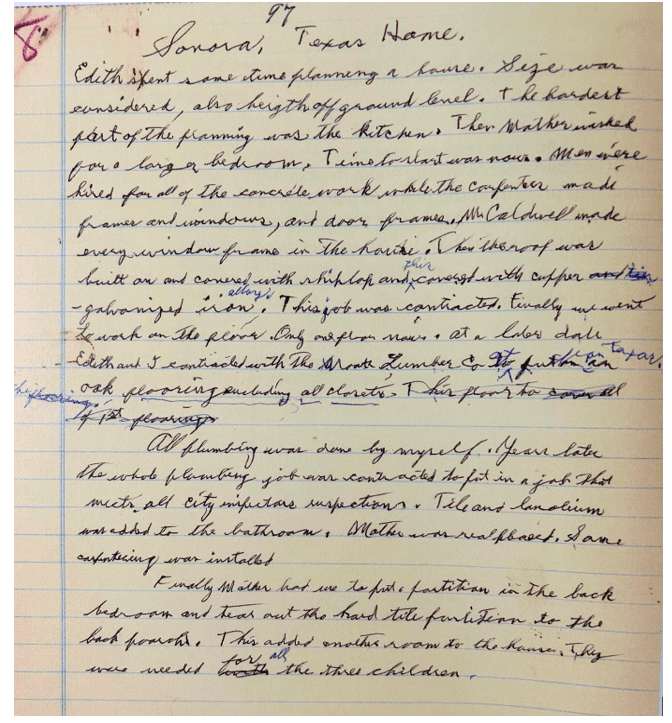

The following was written by Orville when he was in his 80’s. He was putting together notes to complete his family story. Here Orville recalls the planning and construction of the Babcock home on 908 S. Crockett Street. (transcribed on next page)

Edith spent some time planning a house. Size was considered, also height off ground level. The hardest part of the planning was the kitchen. Then Mother wished for a larger bedroom. Time to start was now. Men were hired for all the concrete work while the carpenters made frames and windows, and door frames. Mr. Caldwell made every window frame in the house. Then the roof was built on and covered with shiplap and this covered with copper – galvanized iron alloy. This job was contracted. Finally, we went to work on the floors. Only one floor now. At a later date Edith and I contracted with the West Texas Lumber Company for oak flooring, including all closets.

All plumbing was done by myself. Years later the whole plumbing job was contracted to fit in a job that meets all city inspectors inspections. Tile and linoleum were added to the bathroom. Mother was real pleased. Some carpeting was installed.

Finally, Mother had us to put a partition in the back bedrooms and tear out the hard tile partition to the back porch. This added another room to the house. This we really needed for all three children.

The following excerpt from Kenneth’s book is a description of the family’s new home:

The house was put on a solid concrete foundation under every wall including the inside walls. I found out later that Daddy buried all the water pipes and sewage pipe at least thirty inches deep. That depth would keep the water from freezing in Colorado where he had come from, but it was never that cold in West Texas. I found out years later how deeply the pipe was buried when I decided to replace all of the initial plumbing. We had to spend several days digging that old pipe out.

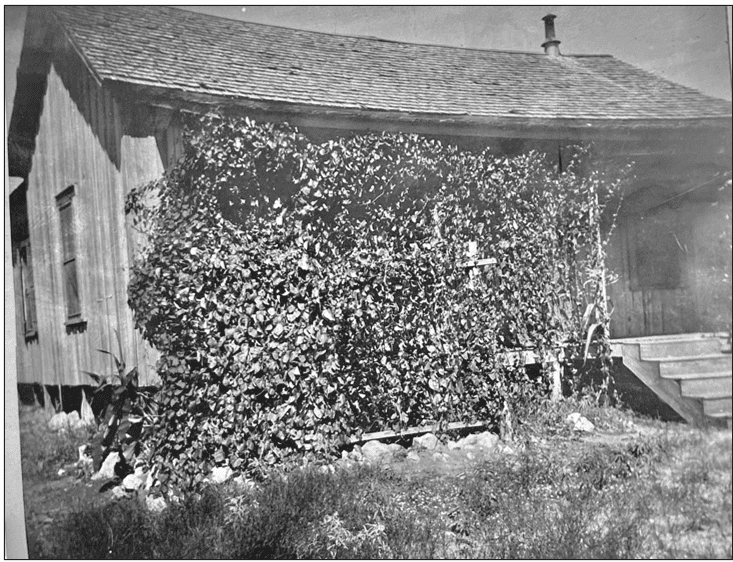

Daddy planted a pecan tree in the backyard just after we moved in our new home in 1927. It was called ‘Texas Prolific.” The tree was trimmed to 7 feet tall and really lived up to its name. In most recent years it produced more pecans than any of the other four pecan trees we had. (In 1950 Kenneth went home and helped harvest the pecans. They sold the surplus of 600 pounds!) In 2002 it shaded an area 800 square feet, stood 75 feet high and was 2 1/2 feet in diameter.

In designing our new home in the days before air conditioning, cross-ventilation planning meant windows, windows, and more windows. There were 33 of them in our new house. Years later I had to paint around those panes in those windows. What a chore that was, as all of them were multiple panes inside and out.

The new kitchen was large, with a nice nook set four feet out on the north side, enough for our breakfast table. There was a fireplace in the living room where we kept the piano. Sometimes it was too cold to practice, so then I had to build a fire in the fireplace. The dining room was large enough for me to easily place eight persons around the table. The back porch was large enough for me to curtain off a small room for my very own. The master bedroom wall joined my room and was large enough to hold a small bed for Edith May. Each year we took in two schoolteachers to room and board with us.

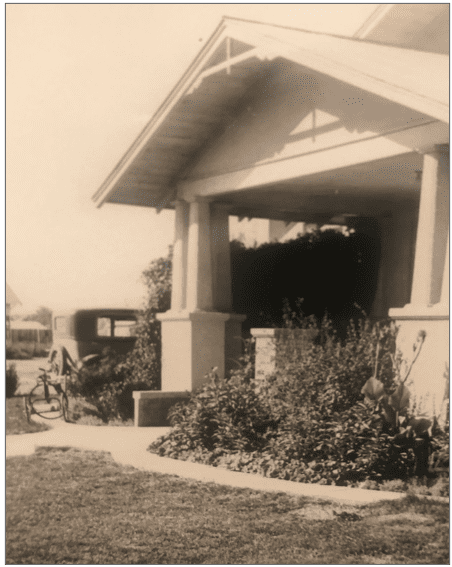

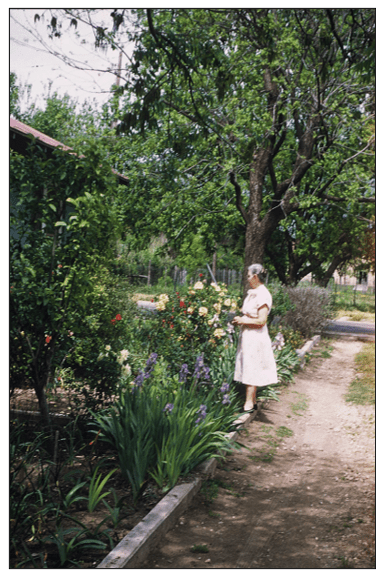

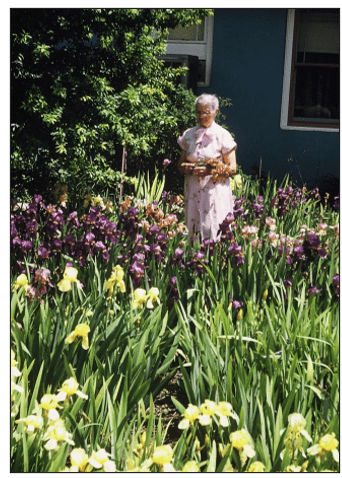

The Babcock home was originally painted beige and later painted blue. It was surrounded by a rainbow of flowers, including tulips, poppies, geraniums, irises, and violets. Many of these plants were purchased from mail order bulb companies. On one side of the house were the sun loving plants and the other side shade seeking ones. A little pool was added for the ducks and migrating geese.

It was common for folks passing by to stop and look at the bounty of colorful flowers in the Babcock yard. Flowers were packed in so tightly one could barely walk between them. They lined the pathways around the house and along the driveway leading to the house.

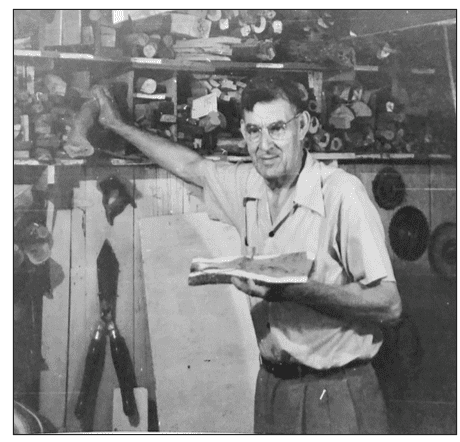

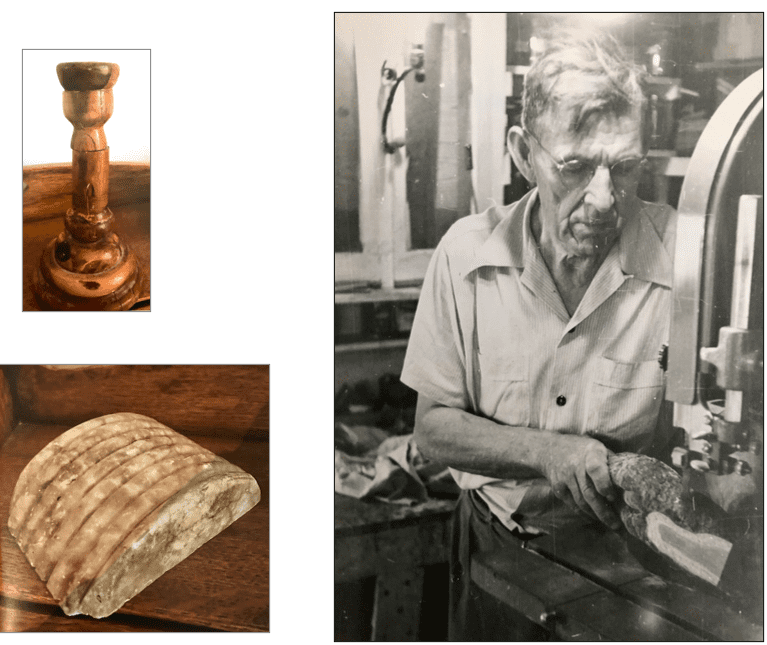

Inside the garage was Orville’s workplace which had woodworking tools and lathes where he made lamps and candlesticks and small tables. He collected all types of wood wherever he traveled, and it crowded the space for the one family car. He also collected rocks and fossils as he traveled. In another area of the garage, he had alabaster rocks that he would grind into beautiful little bowls or candlestick holders.

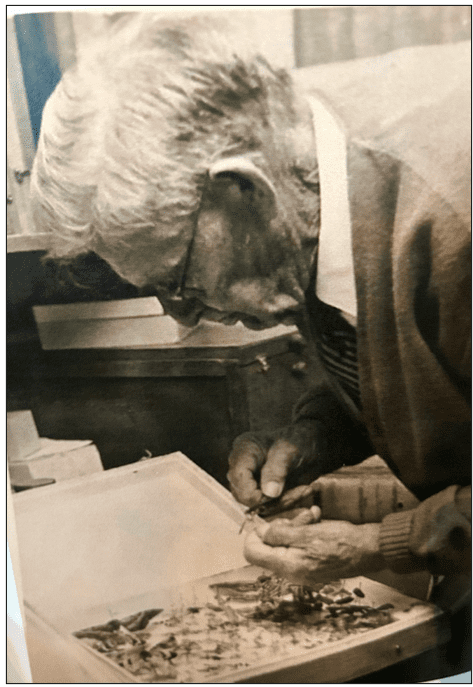

Attached to the right of the garage were about fifteen creaky stairs that led up to Orville’s insect collecting room. Each one had met a fate of chloroform and when dead, a needle pinned them to their individual place in his handmade wooden boxes for the rest of their days. Entomology was Orville’s specialty and passion.

Orville had many interests, among them was music, geology, collecting and identifying insects as he had done since his childhood days in Denver. He had over two-hundred samples of native woods which he gave to San Angelo State College after he retired to display.

Orville had a great sense of pride in showing any visitor who stopped by what awaited them in the room above the garage; box after handmade box of precisely labeled bugs, butterflies, moths, literally thousands! He took great delight when someone would stop in with a bug or insect they wanted him to identify.

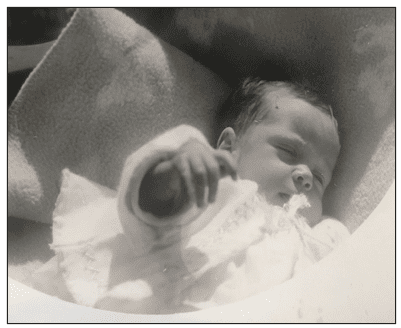

Coming back down the steps to the left was a small grassy backyard with a grape arbor where the family enjoyed backyard picnics. A greenhouse sat next to the grapevines, just off the stoop in the back of the house. A couple of steps from there, a cement slab had Edith May’s baby footprint in it. The greenhouse was built into the ground, so it took two or three steps to walk down into the main narrow walkway inside. There was a musty, humid smell, along with some fertilizer odors that wafted through, and many plants were in various stages of growth, getting ready to be planted outdoors or tucked in pots to be safe from the cold in winter.

To the right of the greenhouse was a fig tree near the back steps, one in the front and one of three huge pecan trees in the back. It was their only son Kenneth’s job to climb the tree and shake the branches so the family could scoop up the hundreds of pecans that fell in the fall.

Edith made delicious pecan pies, as well as fruit pies such as cherry, peach and apple. Any leftover crust was rolled out with and sprinkled with sugar and cinnamon to the delight of Edith May. Her mother’s pie crust recipe has passed down and still used to this day. The pecan tree was Edith May’s favorite tree. She climbed it often, waiting for the train to come by so she could wave at the conductor who was coming into town to collect wool from the sheep ranchers in the area.

The chicken coop was all the way in the rear of the property just past the clothesline where young Edith May helped her mother when she was tall enough to reach it with the clothespins. The chickens provided eggs and a meal for Sunday dinner. Mother, and sometimes Kenneth, oversaw killing the poor hen while young Edith May stayed indoors so she wouldn’t hear the hatchet fall. She hated that part of having chickens.

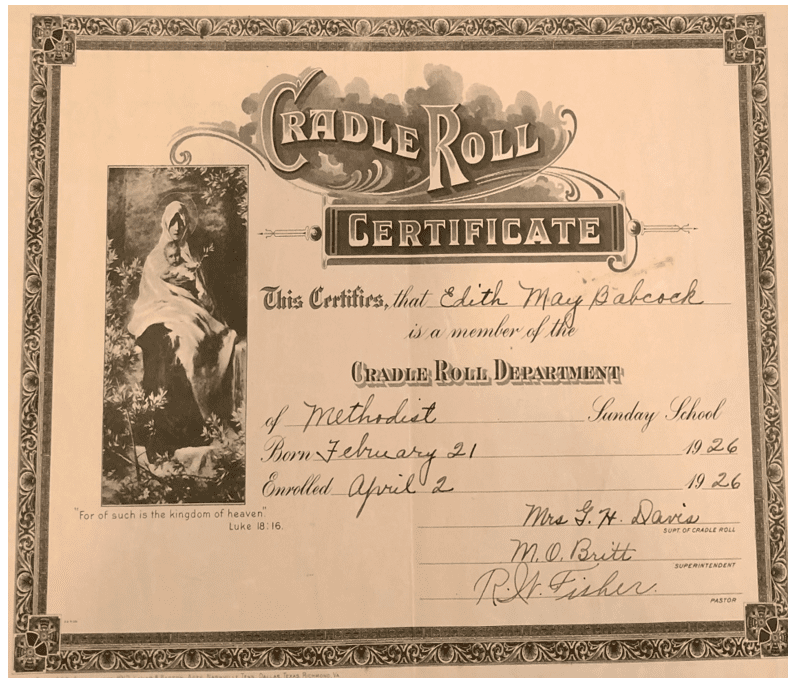

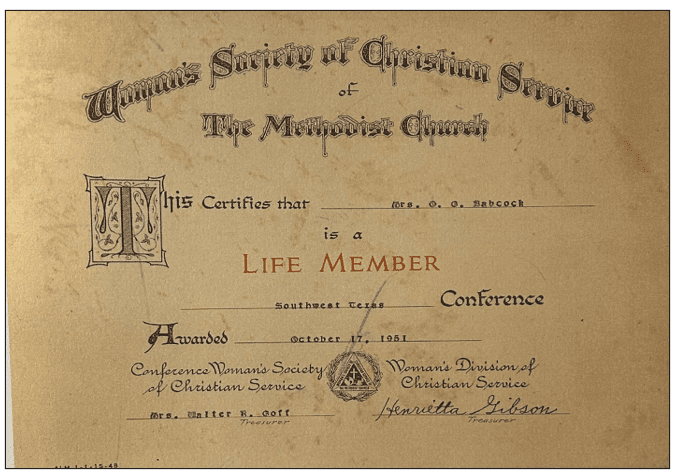

Sunday’s meal followed the service at the First Methodist Church. Orville, as a scientist, identified as a Unitarian. And even though he wasn’t very religious, he still put on his suit and went to church with the family. It wasn’t uncommon for young Edith May to open her eyes to see if her daddy was praying when the preacher asked them to bow their heads. She said his eyes were always wide open, and he’d be glancing around.

Sunday’s meal included the main course, a gelatin salad with fruit cocktail or something similar, refreshing iced tea in green ‘thumb pressed’ glasses and a delicious slice of cherry pie or another fruit Edith had saved up in Bell jars when the fruit was ripe for picking.

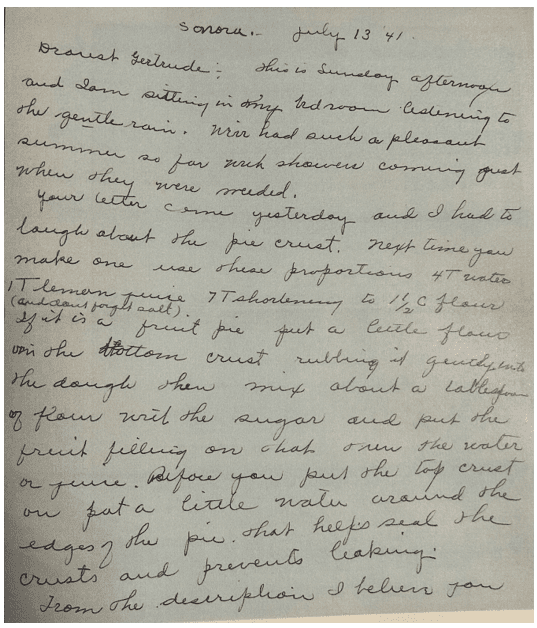

In this letter to Gertrude, Mother shares her fruit pie recipe which has been used by four generations.

Dear Gertrude,

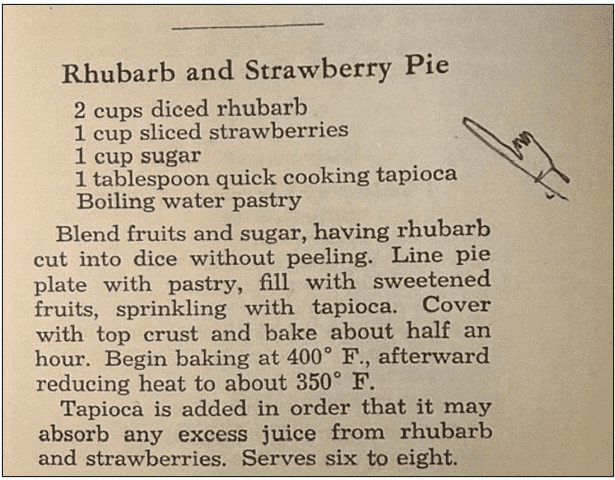

Your letter came yesterday, and I had to laugh about the pie crust. Next time you make one use these proportions: 4 T water, 1 T lemon juice, 7 T shortening to 1 ½ cut flour (and don’t forget salt). If it is a fruit pie put a little flour in the bottom crust rubbing it gently into the dough. Then mix about a tablespoon of flour with the sugar and put the fruit filling on that over the water or juice. Before you put the top crust on put a little water around the edges of the pie. That helps seal the crusts and prevents leaking.

Life for the Babcock family in the West Texas town of Sonora was nothing like where Orville and Edith had grown up in the cool mountains of Colorado years before. But this would be home until their final days.

Edith, a domestic science graduate, started and operated the first school cafeteria in the basement of the old school. Much later as a correspondent to the San Angelo Standard Times, she not only wrote news stories, but feature stories on the pioneers whose tales of their experiences she found fascinating. She wrote, “The pioneer ranchers were a unique breed.”

(Note to reader: Edith Stella Babcock’s newspaper articles are archived in San Angelo Library on microfilm. Orville Babcock’s insect collections are preserved in the biology department museum at San Angelo State and available for research by advanced students.)