“Tell me it again,” Mother, I pleaded, putting my arms around her wondrously soft tummy. She hugged me back and though I was almost too big to fit, I snuggled down comfortably in her lap to hear the wondrous story. It was my birthday, and this was part of the annual ritual in celebration of my birth. What could be more special to the honoree than to hear the details of this most important event!

I knew the details so well, I could easily have told most of it without a flaw, but it was better having her tell it. Having her hold me like this, I could close my eyes and visualize just how it had been. She began…

“It was a cold February day. The coldest day of the year in fact,” she said. “You were not due for another month, and when I began to have a stomachache early in the morning, I didn’t really think that you were about to be born. I thought it was something I had eaten that had disagreed with me. I also had a terrible sore throat and the doctor had given me some medicine for it. Maybe that had upset me, I thought.”

“By the time we got up that morning, and your father had the fires started, I wasn’t feeling any better, and began noticing that the discomfort I was having began coming in waves…that is, about every ten or fifteen minutes. I was uncomfortable. After watching the clock and noticing that this was not just my imagination, I told your father, “Orville,” I said, “this could be the baby.” I didn’t really believe it myself, for my other babies had come when they were supposed to, but somehow, I knew this was it, and I began to get ready. I soon packed my bag, but then I had to get your things. I was still knitting little booties and caps, knowing I had month to go. I really wasn’t ready for your arrival. But since I had baby things saved from your brother and sister, I soon had your little suitcase packed, too.”

“It didn’t take long for your father to get ready. He knew how far we had to go to get to the hospital. It was 66 miles away and the roads were icy for it was still below freezing, and it had rained and sleeted the night before. He was worried. I could tell by the way he rushed around.

“While I was packing, he had been outside putting chains on the car. He was taking no chances of going into a ditch. I took Kenneth and Gertrude to our good friend and neighbor, Mrs. Ridley.” (They were my big brother and sister.) “They used to love Mrs. Ridley,” she said.

“Did you get the lap robes, Mother?” he asked. “I said yes.”

“Then I think we’re ready. I had to pour hot water on the radiator, even though I put the treatment in, but I don’t think we’ll have any trouble with the car now. She’s roarin’ to go.”

“Your father carried the suitcases out, and I carried the lap robes. It was so bitterly cold on that day. I will never forget it. Everything looked so grey. The mesquite and the grass, the sky and the land all looked the same shade. The only things which stand out on the landscape were the green live oak trees. They never lose their leaves, you know, even in winter. With ice on everything, it looked even more grayish silver. It might have been beautiful if the sun had shone on it, but then it looked ominous. I dreaded the trip. But your father and I had agreed that you were to be born in a proper hospital with a good doctor. You were so precious to us. We wanted to be sure nothing went wrong.”

“The road wasn’t paved all the way, so the first 40 miles were on dirt roads. The roads ranchers used to get to their ranches. Every once in a while, we would come to a bumper gate, an invention by the ranchers to protect their pastures of cattle. They knew there were people who used these public roads who didn’t close the gates after they had opened them and driven through. The bumper gate had a pole in the middle, with a gate on each side attached to it. A chain up the middle of the pole was attached to the two gates and twisted in such a manner that when the gate was bumped on one side it swung around wide enough to let the car pass, and then back again to close both openings. It was great fun to bump one’s way through these. But it had to be a gentle bump, or wham! Your car’s backside would get it when the other gate swung around, and that was something a driver wanted to avoid.”

“Your father especially wanted to avoid getting bumped because of my condition, so he bumped his way very gingerly. Finally, we reached the paved part of the road, which would lead us into San Angelo, where the hospital was located and where my doctor, Dr. Mac Anulty would be waiting, for we had telephoned him long distance before we left home.”

Very early in my young life, I also had learned the story of a baby brother, a brother who died at birth. This tragic event occurred several years before I was born. Most women, in those days, had their babies at home, because there were no hospitals in rural areas. Their mothers before them had also had their babies at home, so it wasn’t an unusual event. Rural doctors usually were quite good, attentive, and there were few mishaps. My mother had had two other children before that with no problem. This time she sent my father for the doctor, the only doctor in town, Dr. Blanton. He came quickly, but unfortunately, he was drunk! There was no one else to call. He did what he could in his condition. The baby was a breech birth and was born dead. Of course, I didn’t know the details of the ordeal, but sensed it had been very serious and learned later that she nearly died. Of course, they could never really forgive the doctor for the tragedy, and I imagine he could never quite forgive himself. Some years later he died in a single automobile accident on his way back from San Angelo. He was drunk.

After the doctor had left, my mother became very ill, and my frightened father ran to fetch the only other doctor he knew, a veterinarian. They both worked at the government experiment station which was located in the area. Daddy was an entomologist hired by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to research on screw worm flies which were devastating most of Texas, especially West Texas, and killing the livestock. Dr. Bennett, a fine veterinarian, came and my parents always credited him with saving my mother’s life. Through the years I have always had great respect for people in this profession, knowing that their medical training is not all that different from human medicine.

They didn’t speak of the tragedy often, but the one admonition my parents would make to we three children, was. “Don’t marry a man who drinks, for you can never change him. He will always drink, no matter what you do or say.” The amazing thing to me now, is that I remember so clearly that they never raised the moral issue of alcohol, but rather talked about it as being a dangerous and addictive drug which would affect the brain. The only hint of morality they connected with alcohol was that under its influence, people did things they would not ordinarily do, and this could lead to all sorts of consequences, they said. In my teen years, sex was brought into the subject. “Girls don’t know what they are doing under the influence, and that is how they get pregnant.” I was impressed.

But to get back to my mother’s story.

“We had been driving over three hours at a snail’s pace and had just passed the little town of Christoval when the car began to sputter, and then rolled to a stop. We both got out and could see nothing to cause it to stop. Your father got the crank out of the box and fit it onto the notch on the front of the Model T. He cranked and cranked, but it wouldn’t start. I got back in the car, for I was freezing by now. The wind had come up and even with the doors closed, the wind whistled in through the canvas top. I pulled my lap robe close to my body, and he tucked his in around me and went into Christoval for help. When he came back, he said he couldn’t find anybody. It was Sunday. But he said he had called the hospital in San Angelo to tell the doctor we were stranded fifteen miles out of the city, on the road to Sonora, and to please send help!”

“By then my pains were coming closer, and I was feeling very uncomfortable. I was scared you were going to be born right there and that you would freeze to death. The temperature was about 17 degrees. There was no such thing as a heater in the car even if we could have gotten it started. Your father took off his heavy jacket, even in the cold, so he could try again to crank it better. All of a sudden it gave a jolt and started sputtering…then died. He gave it another long crank, and it started. He threw the crank into the car, jumped in and we were off. “Drive faster. It’s not going to be long now”, I told him. But he couldn’t go much faster than he was. When we were about five miles out of the city, here came the driver from the hospital and the doctor! Your father waved frantically to him. They turned around and led us into town to the hospital.”

“The nuns at the hospital were waiting at the emergency room door and rushed me inside on a stretcher. And in a very few minutes you were born!”

(I always loved to hear her tell this part.)

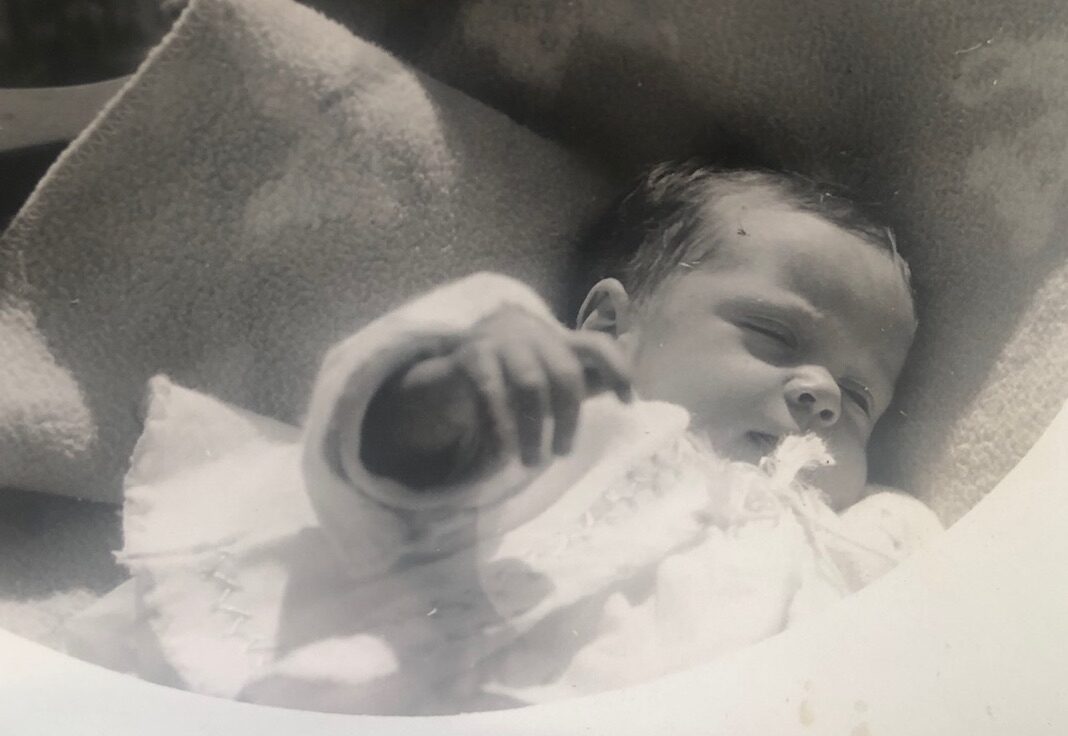

“The Mother Superior brought you into me, all beautiful in your little gown. She had found the suitcase and unpacked it for me. In those days one brought the baby things to be worn right away. She laid you in my arms, and you were the most beautiful little bundle I ever saw, all five pounds of you. Your hair was like a little black kitten’s.”

“I was very tired, and they didn’t leave you long with me. In fact, I was quite sick. The nuns took expert care of me and of you. It was the best nursing care I ever had. It didn’t matter that we weren’t Roman Catholic. They almost never left me alone. We stayed for two weeks, until you were strong enough to leave the hospital, and until I had recovered from my strep throat.”

“Your father left me in good hands and drove the torturous way back to Sonora to see about your brother and sister and to tell them about their beautiful baby sister. Of course, I knew my mother wasn’t telling the truth about my being a beautiful baby. I had seen the pictures and I was about the ugliest baby I had ever seen!

And thus, opened chapter one of my life!