Sonora as viewed from City Hill (1900). City Hill Road is in the foreground.

The community in which I was raised gave me a host of advantages which have followed me through life. It had many disadvantages as well, but I think the good overshadowed most of those, or perhaps they have faded from memory.

I grew up in a world which was quite small compared to city life with numerous churches, museums, schools, businesses, etc. In our small town of 2000 people, everybody knew each other as well as everyone’s business. I could write a paper on many subjects to do with community: funerals, the town drunk, Bull Durham roll-your-own-cigarettes, town gossip, neighbors and caring, Saturday night football, the other side of the tracks, the telephone operator, dreaded piano recitals, the rich and the poor, ‘oil field trash’ and how it changed the community, WWll, a cemetery visit and the play, ‘Our Town’. Many more subjects come to mind as I jot these down. Today, I will write but three comments on drugs, wranglers and horses and a few comments on life back in the late 1930’s and early 1940’s.

Few people had ‘help’ in their homes when I was growing up, but if they did, they hired Mexican girls and women who were available and anxious for work. Ranchers hired Mexicans (they were not called Hispanics or Latino’s back then) as wranglers and usually offered ‘room and board’ a bunk house, a ranch store (a room built for that purpose) where they could buy cigarettes, coffee, frijoles, masarena and some personal items. Spanish goats were kept as a good source of meat for barbecuing cabrito. Most ranches were a half day’s drive to and from town. The ‘help’ did not, as a rule, have their own transportation and would be picked up or taken to town as needed, unless they happened to be illegal ‘wetbacks’, in reference to swimming the Rio Grande. Ranchers, as a rule, provided a Mexican family with living quarters, too. The wife usually helped with chores in the rancher’s home and became somewhat of a companion or company for the isolated rancher’s wife. Likewise, the Mexican woman was isolated as well, who was far away from her extended family. Good friendships and respect for each other were the usual, though there were instances of abuse and neglect.

Children of both families played together and learned each other’s languages. Seasonal help was needed as well, and some wandered in from across the border annually to work on the same ranch year after year. It was illegal but widely accepted. The ranchers needed them, and they needed work. No questions asked.

A family outing along the river (1939)

Orville, Edith May, Edith, Kenneth and Marie Watkins

The most hated part of this system was the Border Patrol, which at times put up roadblocks that were not very effective. There were ways to get around this nuisance by word of mouth and avoidance. Nobody liked them and they never became accepted members of the community where they lived, though they were just doing their job for the government. They were busybodies as far as the ranching operations were concerned. They needed help that wasn’t available from the local population. When the US entered WWII, there was a desperate shortage of American workers left at home, for they were all being drafted. Meat was a prime item for the armed forces, and it was provided by ranchers from around the country. We didn’t hear much about the Border Patrol in those days.

This was all long before drug use became a problem, though it was well known that some Mexicans grew their own marijuana in small gardens behind their tiny houses along with chili peppers, onions and corn. To my knowledge, no one in town gave much thought about marijuana. It was considered to be a cultural habit among some Mexicans. I equate the use to the South American Indians who chewed beetle nut, which stained their teeth, but they were otherwise unharmed. Primitive people in all parts of the world use drugs or intoxicating beverages both for ceremonial and medicinal purposes, and socially, but never to the extent to which Americans are into the drug culture. Never would I advocate its use, but it does put their moderate use in perspective compared with ours as a nation. Even now, drug providers in Colombia and Mexico, as a rule, do not partake of the very drugs they sell, though they are presented to their buyer in the US and elsewhere in stronger and more dangerous forms in order to cause greater addiction.

This could lead to a commentary on American drug use and how entire economies in Central and South America now rely on drug money and, of course, in poorer countries in the Middle East. Only when dollars entered the scene did the drug problem explode along with our demands. Wouldn’t it be better to legalize drugs, provide help for addicts who register their addiction and receive free treatment? It certainly wouldn’t be as costly as the drug war has been. Crime would diminish rapidly without the almighty dollar which is a link in the process. After a 30-year war in Colombia perhaps it is time to look at the problem in a fresh way. I don’t believe it would get any worse. The pity is politicians won’t touch it. It would mean sudden death to their careers. Try it yourself and see how far you get. You won’t be popular. It would be as hot a subject as Freedom of Choice, only more so. Dare we look back at the history of our country and recognize the problems in our past.

I was about eleven years old when Mother once hired a Mexican woman to help out for the day. The woman arrived and worked very hard. She was mopping the kitchen floor, when I saw her take off her tam (headpiece) she was wearing. She said she was hot. She stopped to wipe her face and said she would go outside to cool off. Later I came back into the kitchen for something. She was mopping the floor again. Suddenly, she stopped again to take off her black tam and wipe her brow. I noticed she had wooden matches stuck in her black hair which was tied up in a knot. Then I saw a cigarette. It was behind her ear, not burning, but burned on the edges, like it had been lit before. I told Mother, but she didn’t say anything (she hated tobacco). About five minutes later this woman suddenly threw down her mop. In doing so, she knocked over the bucket of water and ran out the back door, arms flailing in the air, screaming in Spanish, “Oh, my baby! My baby!” And she was gone. We never saw her again. “What happened?” I called in disbelief. Mother was calm and said, “Oh, I think she must have been smoking marijuana.” That impressed me and was my first introduction to drugs and what they do to people. I was about twelve years old. Little did I know what was coming forty years down the road in our society.

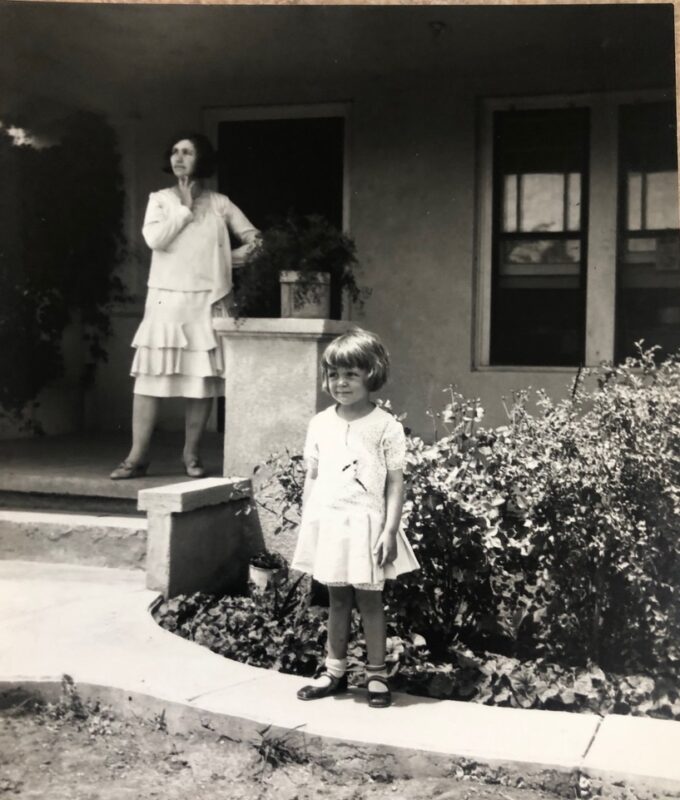

Six year old Edith May and her mother at their home on Crockett Avenue.

There would rarely be a murder in the Mexican part of our town. When there was one, it was usually attributed to alcohol or marijuana. But, by today’s standards, crime was pretty benign. It was not a common occurrence. We heard little about the drug, although there must have been isolated cases.

The ‘drug’ that killed people in our town was alcohol. Other than tobacco, it was the drug most used. These weren’t called drugs and seldom are today. The town was silently separated by those who drank and those who didn’t. I seldom heard anyone talk about it, but it was pretty obvious. I guess too much was said during prohibition when people made their bathtub gin.

My parents never told me it was a sin to drink or smoke but explained, even then, that both were dangerous chemicals and alcohol would cause one to do things they would never do otherwise as well as being harmful to the brain. I remember when I was a teenager and some of my friends began to drink, my mother again reminded me that when people drink, they sometimes lose their inhibitions and do things they would never do otherwise. I got the message. My family members were near teetotalers, except for a bottle of Muscatel wine we shared around the table at Christmas or a special celebration. Even the children had a thimble-size taste, but of course we didn’t like it, for it was very sweet. My father had a good friend in the border town of Del Rio who owned a winery and asked occasional advice for his grape vines. Pest control companies were unheard of, but my father was an entomologist and had been sent to Texas by the Department of Agriculture to work on problems occurring in the sheep and goat industry as well as cattle. He also helped friends with their pest problems. Wine arrived at our house every Christmas for as long as I can remember. I think the winery is still run by descendants of the original owner.

Most of the fatal accidents in our town and surrounding areas were caused by drunk drivers. Establishments were banned from selling mixed drinks. There were no bars and no alcohol found in restaurants. If people wanted to drink, they took their own bottle bought in another county, set it on the table and, as was the custom, they “killed’ the bottle before leaving. If several members of the party brought a bottle, the consequences were often disastrous. It took a long time for those laws to change.

I didn’t live on a ranch but often accompanied my father to area ranches to demonstrate the use of dipping vats and how to use a wet Sulphur which he perfected to kill ticks and other harmful pests. My favorite part of the trip was to have a chance to get to ride a horse. Mexican wranglers had often helped me learn to ride. They knew the horses and usually picked out a tame cowpony for me. They showed me how to handle the reins to steer a horse. I was taught never to use the saddle horn to stay on the horse. It was a sure sign of a drugstore cowboy. One day, soon after we arrived at a ranch, we saw all the cattle rounded up and horses either tied to a tree or in a barn lot.

Edith May riding on black quarter horse.

They had been rounding up cattle for dipping long before dawn and the horse they offered me was apparently in no mood for a joy ride. He didn’t want to leave the barn in the first place, but I confidently steered him out toward the open pasture. I fought him for over fifty yards determined that we would go have a nice sprint. One learned to stay on by gripping with one’s thighs and pressing hard into the stirrups. I was thirteen years old and had no sense of fear and very little sense! No doubt he sensed he had a poor mount on his back who was so light that he could darn well get rid of her for taking him away from the barn, which he promptly did. After a terrifying toss into the air with the landscape circling around my head, all the way down I landed hard on my back gasping for air. As I focused my eyes again, I could see the wranglers and cowboys laughing, even my own father, all leaning against the corral fence as I lay dying! I was furious. How could they! My father came over and helped me up. In a few minutes I could breathe again. Everything hurt. No broken bones, only wounded pride and a very sore body. The mistake he made was not making me get right back on that horse. To this day, when I ride, I know the horse senses a deep-seated fear, no matter how I try to hide it. I think of that day, when I thought I did everything right, overconfident, happy, a budding cowgirl, or so I thought. I still loved to ride after that and never missed an opportunity, but the horse always seemed to know my shameful secret. I hated to get an old nag that wouldn’t run. I hated horse trips where you are all lined up and plodding on a well-worn trail. There is nothing like being out on a ride in the midst of a cool spring day in Texas. I’m glad I still have that memory.

I was lucky to be able to continue to ride with friends on their ranches and had only one other hair-raising experience when a friend and I were racing quarter horses at her uncle’s ranch. Her aunt had said we could ride, but she admonished us not to go to their racetrack where they trained horses for quarter horse races which was legal in Texas where pari-mutuel betting was still allowed. We rode off in that direction. When we saw the track, we couldn’t resist the temptation and agreed not to tell. We raced around one whole lap as fast as we could. It was obvious the horses loved to race. They were bred for it. We were galloping faster than I had ever gone before! What fun that was to ride on a real racetrack.

All of a sudden, they left the track and headed Hell Bent for home, racing! The barn was about two miles away from the track. They took the shortest route where there was no sign of a trail. We ran through bushes, under trees, passed cat claw, over prickly pear, under mesquite, circled around bushes they couldn’t jump, and it was all each of us could do but to hang on for dear life, keep our heads down and pray. There was no way to stop them. We came in neck and neck, a dead tie! They stopped right at the barn. Again, the Mexican wranglers were laughing. They knew what we had done, and I think they were impressed that we hadn’t fallen off. Right then and there they gave us a lesson on how to stop a runaway horse. “Saw with the reins as hard as you can, back and forth to move the bit hard which will hurt them, pulling back hard at the same time.” I have never raced a horse again or had one run away. I stick to a slow trot or a comfortable lope. But of course, our horses knew they could get away with it that day. It was as if our laughter sent a message to the other horse, “Let’s do it and scare those girls to death.” I don’t remember being scared, for I was too busy hanging on. Somehow, we sensed it was almost a life or death matter. We never told her aunt, or our parents until years later. Actually, in retrospect, I’m rather proud of that run.

My community was warm and nurturing and included not just the town, but the surrounding area. It wasn’t a perfect one, but I learned about life and lived it. With the help of the community, I grew up. I made mistakes, but as Alvin Toffler said, “Community is our keeper.” We need it. Our children need it. We need each other. We are shaped by where we grow up.