“It’s true!” she said. “I may be 70, but I certainly don’t feel like it. I’m still 25 inside here,” as she pointed to her head and smiled at me. My mother’s skin is so lovely, I thought, as I smiled back. She wore no makeup, never did, and her hair was softly braided and the braids were still dark brown. Only a few smile lines showed around her eyes and mouth, but her skin was virtually wrinkle free. She wore no jewelry. Her deep-set eyes looked warmly into mine, as if expecting an answer. “Do you really?” I asked, “Even after three children and all your life experiences?” How beautiful she is, I thought, even at her age. As hard as she had worked all her life, how could she feel young inside, I wondered? She said, “You’ll understand, someday. I know I’m getting old. I don’t want to grow old. Nobody wants to, especially if they don’t feel old. Time passes so quickly.”

Edith Stella Knoll Babcock (1962)

I felt guilt, then. Guilt from taking my children so far away for two years, and myself as well. Time was passing. She looked the same to me, but my daughters had been babies when we left, and now they were talking, playing, running, jumping little girls. Soon they would be schoolgirls and then young ladies. Is that how they, the aged, measure time, I wondered, by the rapid scale of growth of children? I had seen several of my parents’ old friends in the community when I had walked downtown the day before, and it was reassuring to see them looking the same. Everyone looked the same. They had looked the same since my own childhood. I was the one who had aged.

Mother was still wearing her apron. We had been baking cookies that morning and were now taking a break before starting lunch. I recognized the pattern of the material it was made from. It once had been a dress which mother wore several years ago. How like her, to save the skirt to make a pretty apron. She never wasted anything. She made beautiful quilts from scraps from all our clothes she had made. I remembered boxes of scraps. And a linen closet full of beautiful quilts.

Edith Stella Babcock was known for her delicious

baked goods, particularly the meringue pies.

A portion of one of mother’s beautiful quilts.

This was the last quilt she made before her passing in 1968.

As we continued chatting, I thought to myself, “I had forgotten how much I loved my childhood, my home, my family, my hometown.” I had fond memories. Perhaps it was because I was the ‘baby’ of the family and had a more relaxed ‘bringing up’ in easier times than my brother and sister. They used to tell me I had it so easy and that they had to blaze the trails. I was also the homebody, the one who got homesick and cried over good-byes. I was born late in my parents’ lives. They were in their early forties. I was probably a surprise, but I often heard my mother say, “It’s wonderful having a child to raise. It keeps me young.”

The birth of baby Edith May completed

the Babcock family.

Later, when I was in high school, she said, “I love being around the young people. They are so enthusiastic and alive. It keeps me on my toes.” Indeed, she mixed easily with my friends; they enjoyed talking to her and felt at ease discussing problems, fears of war, their futures, their careers. Yet, she didn’t get down to their level; she treated them with respect and they, in turn, respected her. Never did she forfeit dignity or maturity for anyone’s sake. She was much older, or so I thought, than the parents of most of my friends. But she was also more patient, understanding and less critical than they were.

As we talked, I remembered things that had happened during my own childhood. There were memories of our backyard, my playground. There was the grapevine where I hid treasures up in the thick leaves in the arbor. It was still the same, and I could see it from her bedroom window. Beyond it was the utility yard where firewood was kept, and the ‘execution log’ where they killed the chickens. We always had our own chickens…fresh eggs, fried chicken and roast hens. I was in college when I discovered very few of my friends had ever seen chickens except in the supermarket. Among my earliest memories were those of the baby chicks arriving, in flat cardboard cages, with little holes in them. What excitement to see their furry little gold bodies and hear them cheep cheep. Mother took charge of the chickens. I gathered the eggs. Mother decided which was to be killed and I watched as she gently held its neck on the log, stretched out, for a quick clean cut. Then its body would go leaping around the dusty yard, and I would be amazed as I saw its lifeless head lying on the other side of the log. She confessed she never liked to do it, but somebody had to, she said!

Edith May playing in the chicken yard.

Almost before I was old enough to remember, we went through the Great Depression, but since my father worked for the government, he didn’t lose his job. We had enough to eat. Mother knew plenty who did not, and she used to feed the hoboes who would come through town. I barely remember them coming to the back door. She kept a special tin plate and cup, and a knife and fork for them to use. She always had them do a little work, such as to chop kindlin’, hoe weeds, or stack wood. Then she would bring them a dish of whatever we were having. Word must have gotten around, for it was not an unusual occurrence for several to come by each week.

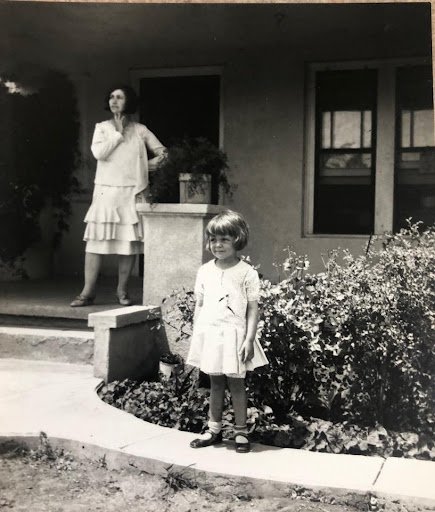

Edith May with her mother on the front porch (1932).

We didn’t have much money, but we were rich in the important things. We had books to read, a Victrola with a nice collection of classical records (My parents didn’t believe in ‘popular music’.). We had a secondhand piano which was regularly tuned. Our family was close, and Mother was the main force – the mender of souls. She was the one we all turned to, even my father. She was my comforter, playmate, friend. She had a comfortable lap, warm hugs, and a sweet smile. She could be stern but not often. I grew up knowing that anything I did would reflect on her, good or bad, and it was I who suffered if I did wrong, knowing how much I had hurt her. It was a hard cross to bear and an incentive to try and be good.

When I was eight years old, I became gravely ill. It was diagnosed as the dreaded Scarlet Fever. Our house was put under quarantine, and my brother and sister were boarded with friends and couldn’t come home for the duration of my illness. My father rented a room and could only come to the door to deliver groceries or mail. Nobody could come to our house but the doctor who came every day. My fever soared and stayed there for days. My throat was painfully sore. My body ached. Mother sat by my bed, putting cold compresses on my head, my arms and legs, to bring the fever down. She rubbed my limbs and my back. She gave me water, almost forcing me to drink. “The doctor says you must have eight glasses a day”, she would plead. They burned my schoolbooks and my toys and most of my clothes. All this seems hard to believe now when a series of simple penicillin injections today will stop the disease before it gets started, known today as ‘strep throat’. But I broke out in a rash, my skin itched and the days turned into weeks. Sheets had to be changed daily for I would have chills after the sweating. Mother seldom left my side. When I began to improve, she gave me a bell to call her with if I needed her. She followed the doctor’s orders all the way, for he warned her of possible heart damage. I began to get well. There was no permanent damage. When I felt like playing, we played quietly together. She brought out the old Sears Roebuck catalogue, and we cut out paper dolls, entire families and all the things they needed. We had a shoebox for each family, and it contained their clothes, furniture, dishes, lawn mowers…everything. She read books. She told stories. She helped me draw pictures. We learned the states and their capitals just for fun. When I didn’t feel like eating, she gave me crushed ice from a spoon and later jello. She made milk toast, a treat her mother made her she said. It was buttered toast sprinkled with sugar and cinnamon with scalded milk poured over it in a bowl. This she would feed to me by the spoonful. I loved it.

Edith Stella Knoll

Age 14 (1899)

After the lights were out at night, she would tell me stories of her childhood near Berthoud, Colorado. I would say something like, “Tell me about the time the horse ran away.” She would laugh and begin. “I was about ten years old and wanted to ride one of our big plow horses, you know, just get up on him and walk around. He was so wide I could hardly sit astride. I was riding along the irrigation ditch on our farm in Colorado and was daydreaming. About as far away as our house is to the street in front, there was a train track. Suddenly the train appeared, and the locomotive let out a shrill whistle. That did it! The horse was so startled he started to run with me on his back. He began to race the train. I hung on for dear life, screaming and grasping his mane. My hair pins were soon shaken loose and my long hair fell down my back and was soon streaming behind. As she talked, I could see her racing along, scared to death, yet not giving up. She held on until the train ‘won’ the race. I knew the story by heart. Her father and brothers came to her rescue and helped her down. Then, they led the horse back to the barn.

Edith Stella Knoll Babcock (second from right)

with her Colorado family in the summer of 1919.

Mother was one of ten children, raised on a farm on the eastern slope of Colorado. She was born of pioneer stock in 1885. She had one living sister and lost another to diphtheria. Few families escaped this dreaded disease. She herself nearly died of whooping cough as a child. I had heard many stories of her childhood. Another favorite was the story of how they harvested ice. Every winter the family would go to the big pond after it was frozen about a foot thick. Her father and brothers would cut the ice into large chunks and haul it back to the farm in a wagon where they would store it in a cellar between layers of straw. It would last through the spring and summer, and up into fall when the next freeze would come. Milk, cheese, potatoes and other food was stored there. They even made ice cream!

She told me stories about her big sister, Nora. She said Nora sometimes resented having to braid my mother’s hair and would jerk it and pull it. The two girls had to do the dishes every day, not only for their big family, but for the hired help who ate in the kitchen. How she hated to do the pots and pans, and they would soak them until their mother made them scrub them. “Oh, how we dawdled,” she would laugh. “It wouldn’t have been nearly so bad if we had just gotten to it and finished the job.”

She loved to tell funny stories on herself, how she would hide under the table and scare her aged grandmother by jumping out and saying “Boo” and how cross she would be, or the trouble she would get into for stopping on the way home from school and skating on the pond too long instead of coming home as she was supposed to do and doing her chores. She walked or skated on the pond nearly four miles to school with her sister and brothers when there was no harvesting to help with.

Edith Stella (right) and Nora, her older sister

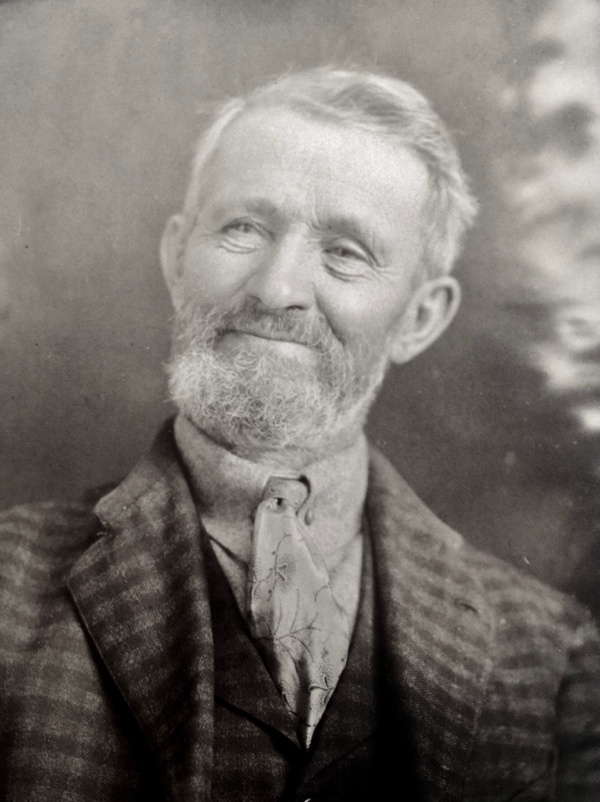

Henry Knoll (1916)

Edith May’s grandfather on her mother’s side

She would sometimes laugh until she cried over some experiences, such as the time she had to watch her little brother, Rennie. He was about three and had dirtied his pants. She was so cross she made him take them off and stand in the irrigation ditch while she ‘cleaned’ him with a broom. Her mother was so angry with her when she caught her.

She became more serious when she talked about her father who she said was a funloving, kind, and hardworking man. “He had a great sense of humor,” she told me, “and he really enjoyed life.” Most of all he enjoyed the family and children, and more than once he told her, when she was grown, “Enjoy your children when they are young and at home. Soon they will all be gone. The happiest days of my life were when my children were at home, and we were a family.”

I never knew her parents. They were dead and the farm was gone by the time I was born. We lived in faraway Texas, so I barely knew my relatives in Colorado. Once, I remember we did go back for a reunion, and during this time Mother wanted to go back and see the farm. We drove down the dusty road in our new DeSoto, not far from Berthoud. We came to a stop at the broken-down gate which blocked our way. Ahead was a big old two-story house, no yard, no shrubs, and a few dead trees around it. Old farm machinery was dotted here and there. A dog barked. Nothing else seemed to be there. No people about, no animals, no crops, only dust and a few tumbleweeds. We all got out to look. As we stepped on the dust, it flew up around our ankles. Mother began to cry. I had almost never seen her cry and instinctively reached for her hand. I didn’t understand, and yet I think I did. “You don’t know how pretty it was. I loved our farm. There were pretty poplar trees lining the road, and the barns and house were painted and neat. The apple orchard was over there,” she pointed beyond the old, dilapidated yard buildings. She couldn’t go on and we all turned and got back in the car. Dust had settled onto the tears and her face was streaked with mud.

Rusted farm machinery at the Knoll family

farm outside Berthoud, Colorado.

Inside the Knoll family barn

All the way back I thought of her, so alone without her parents and her sister and brothers all scattered. She only had us three children and my daddy. No wonder she was so sad, I thought. Is this what happens when your parents die? I was in misery, too. “Dear God,” I prayed, “Let me die first before any of them. Don’t let Mother and Daddy die before me and leave me.” I knew God could hear me even if I didn’t say it aloud. I squeezed back my tears quickly before anyone could see. I had a secret pact with God and felt better.

When my mother was sixteen years old, she left the farm to go to school. She boarded with a family in Longmont, Colorado and in return helped with the children’s schooling and some household chores. She wanted an education and her parents agreed to let her live there since there was no high school near the farming community. Her sister, Nora, married young and already had a baby. She seemed very happy and married a man who had a large farm. But my mother had other plans for her life. She wanted to go to college in faraway Fort Collins at the Agriculture and Mechanical College to study domestic science, one of the few professions open to young ladies at that time.

She was accepted and was a serious and ardent student. She was the only one of her family to go to college and had to work her way through. She taught children as a governess and also worked summers at a dude ranch in what is now Rocky Mountain National Park. To her, this was as much a real vacation, much like that for college students who work today at the National Parks. I remember seeing photographs of her and her colleagues on the steps of the famous old lodge with their long dresses, pinched-in waists, and bouffant hairstyles of the day, all with very happy smiles on their faces. After the hard life on the farm, it must have been fun for her

Edith Stella Knoll’s college graduation portrait (1911)

Colorado State Agricultural College, Ft. Collins

In college she studied all the sciences, physics, biology, math, geometry, Latin, history, literature, and German. She became very close to her professors and kept up with them for years, some until they died. She met my father in one of the classes. He was a student in agriculture studying entomology. Of course, she also studied domestic science; sewing, food preparation, home nursing care and related subjects. My father was an amateur photographer and took numerous pictures of my lovely mother. It was easy to recognize in her eyes from those photographs that she was a woman in love. He graduated a year earlier than she did and took a job in Baltimore, Maryland. She joined him there the following February after her graduation, and they were married in the home of a friend on February 4, 1912. What a long journey it must have been by train across the continent. Away from the mountains of Colorado to an Eastern city where she knew no one, only the friends he had made during his brief stay there. Her entire belongings accompanied her in a trunk.

The Babcock family home located at 908 S. Crockett Avenue.

(Note the 1930’s style car in the side driveway)

Ten months later a daughter was born and her dreams to be a county agent or a teacher faded. They had moved to Minnesota where my father was a professor working at the University of Minnesota for a year. Later, because of my father’s allergies, they moved west again. After a brief stay in Colorado, next they moved to Dallas where he took a job with the United States Department of Agriculture. By then another baby was born, a boy. World War I was over, and in 1920 the government moved the family to the little West Texas town of Sonora, ninety miles from the Mexican border. Sonora was as dry as Colorado was lush. Mesquite trees provided the only shade except for a few scrubby live oak trees. I was born six years later in 1926.

They were outsiders in this ranching community. They were considered ‘Yankees’, not Texans. But soon became viable members of the community, my mother especially. She played an important part in the coming of age of this little town with wooden sidewalks, tobacco spitten’ cowboys and pioneer ranch women. Life was hard for everyone, and there wasn’t much room for outsiders. Mother became active in church work and saw the Methodist Church come into being. She taught Sunday school and sang in the choir. She opened and managed the first school cafeteria. She formed study groups, a music club to study music of great composers, an art club to study great painters, and she worked in the library to help fill the lonely shelves with books. She was busy not only in the community, but in raising her three children. Meanwhile, my father travelled from ranch to ranch in this vast country, gone for days at a time, educating ranchers on the eradication of the fatal screw worm fly which plagued the southwest, killing thousands of head of stock as well as other harmful creatures such as ticks and lice.

First Methodist Church of Sonora

The Babcock family’s church home, and the location of

Edith May’s marriage to Robert H. Kokernot in 1946.

Edith and Orville loved and nurtured their garden.

Irises were some of their favorite flowers to grow and share.

Mother did all her own housework, including the washing and ironing, baking and yardwork. When Daddy was home, he helped with the yard and even built a greenhouse for they both loved plants. This was unheard of in this dried up world, and people interested in seeing what they did began to drop by. Mother shared her cuttings, gave away plants, shared bulbs with them which they had ordered and planted with regularity. Mother contributed flowers with the church for weddings, funerals, Christmas, and Easter. She always had an abundance of asparagus fern to offer for baskets of floral arrangements for the piano recitals which were to come. People would drive by the house just to see this small oasis in the desert. Trees began to grow around our house, pecan trees mostly, and these became my hideouts, my ‘airplanes’ and ‘horses’. I was Buck Rogers, Tom Mix, Tarzan and other radio and comic strip heroes. We boarded teachers and they were wonderful! Our table resounded with conversation and laughter. This was my expanding family. I was without ‘kinfolks’ but this was almost as good, even better perhaps.

When I started school, Mother had more spare time and she decided to learn to play the piano. Daddy bought a second hand one and we all took music lessons. The piano teacher came to live with us from San Antonio and taught us and many children in town who wanted to study. I suspect she lived almost free at our house in exchange for our lessons. This was during the depression years. Daddy was the only one who didn’t play piano, but he played the violin and sometimes we would try to accompany him. He also played in the San Angelo Symphony regularly. Mother learned quickly and was diligent in her practice. Then she decided to learn to drive. She was so small that I didn’t think she could see over the steering wheel, but she did. Not many women in her age group could drive. Years later I realized what a life span she had lived in terms of transportation and other inventions. Born in 1885, she grew up with the horse and buggy, then the first car was invented, then the airplane, and of course the Zeppelins, finally the jets and ultimately ‘Sputnik’. Would that she could have lived to have seen the moon walk, but she died one year before. Some of the world’s greatest inventions and discoveries were made during her lifetime.

She was so interested in new discoveries, new feats, and would have loved this era of space physics, computers and the like. But she had no patience for non-progress. She hated the segregation she found in Texas. In West Texas it was not so much against the blacks, of which there were almost none, but against the Mexican Americans. She threatened to resign from the First Methodist Church if the son of the Mexican janitor was not allowed to come into her Sunday school class, and the janitor and his family allowed to attend the church service after. (They relented, amidst wagging tongues and shaking heads which she ignored.) She held her ground firmly, but peacefully, without a scene. She voiced her disapproval at the segregated schools. The Mexicans attended school across the ‘draw’ and the whites the better school in the better section. She lived to see the anti-segregation laws passed and the other school across the ‘draw’ dissolved. She lived to see one of those Mexican American children become the school valedictorian, and she rejoiced. She lived to see the high school football team become a championship team with many of its team members belonging to the Latin race. Racial barriers were finally coming down.

Mother decided to learn to swim one summer, at an age few people learn to do anything new. She said she had always wanted to learn, so we taught her. In those days there were no pools, but we swam at friends’ ranch tanks, kept clean for that purpose as well as to water stock. They were concrete and stone and made very handy pools with a wide walk around the top.

The next thing she learned to do, to all our astonishment, was to type. She bought a chart and taught herself. Soon she was writing local news stories for the weekly newspaper; weddings, parties, deaths and a few special articles on people or happenings. She soon grew bored with the petty details of who wore what and when and who attended and began sending stories to the daily paper in the nearby city of San Angelo. She wrote for The San Angelo Standard Times for twenty years as a local correspondent and, in doing so, did a wonderful service for the history of the area. She wrote numerous features on local people and color. Her salary, a few cents per line, which she had to clip and paste up and send in, for her pay. Yet, the editor seldom changed a word. She had a natural ability for editing her own works without formal journalism training. She didn’t do photography but used local amateurs. She turned out some really first-class feature stories. With the money Mother made, she began to buy articles she had never felt she could afford before, including a gradual collection of fine crystal and silver. She loved to entertain her friends simply, and enjoyed her various clubs and church groups, and often used her new crystal and silver at those times, but also at festive family gatherings.

When I went away to college at age seventeen, she said, “You’ll come back to visit, but you’ll never come back to live.” I doubted this, but it was true. My heart was at home in my small town with my parents. My mother was ever in my thoughts. But she raised me to go out into the world as she had done. I never went back home except to visit. I lived 10,000 miles from home for seven years, then two years in South America, but she didn’t complain. She published some of my letters in the newspaper, for South Africa was an interesting topic she thought, and my letter should be shared. She had vowed she would never fly on a commercial airplane, but we did persuade her and my father to visit us while we lived abroad in South Africa. They had never travelled out of the States before.

Truly, she was young at heart, always ready to learn, seeking adventure and looking forward to tomorrow. When she died, she left me with a heart full of memories and values to pass on to my children and their children. She lived with patience and courage, strength and understanding. She was a good wife, a loving wife and mother. God let her die first, but not before her time, and for that, I was grateful. The pain of her absence has been eased with the love she left behind.

Orville holding their first grandchild, Sherry Babcock, Kenneth's daughter.