Daddy brought in another mesquite log to lay on the fire. “That should hold it for a while,” he said, as he set the fireplace screen back on the hearth to catch the inevitable sparks from a new log.

I moved closer to the fire and rubbed my hands together. The living room was cold but warming up quickly. It was the day before Christmas, and we had lots of things to do. I looked down at my new long stockings that Mother ordered for me from the new winter Sears Roebuck catalog. I pretended to hate them, but today they felt good. Little girls in the 1930’s didn’t wear slacks nor did their mothers. Secretly though, I longed to be a boy, for I loved playing with cars and trucks and cowboys and Indians. That’s why I needed long pants! I played ‘house’ and dolls, too. My collection of paper dolls was fun, and Mother showed me how to enlarge my collection by cutting out pictures from our old Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward catalogs, such as furniture and toys, tricycles and bicycles, red wagons and even ‘friends’ for my paper dolls. I kept them in several old shoeboxes. But today I was thinking about the letter I wrote Santa with Mother’s help, of course. “Dear Santa Claus, I have been a good girl. I would like a baby doll for Christmas. Mother said you know where we live. I love you.” Then I sent it to Santa by tossing it into the fireplace where it was caught up by the smoke and carried up the chimney and off to the North Pole. That’s how our family mailed letters to Santa. Kenneth, my big brother, said it works.

Our Christmas tree stood in the corner by the bookcase where Daddy always put it. My sister, Gertrude, was home for Christmas after being away at college all fall. I was glad she was home, for I had missed her so much. Mother had waited for her to come home so she could help us decorate the tree. Gertrude was very artistic. We all worked together to make it beautiful. The last decorations we added were the icicles. Gertrude wanted to do them, for she always hung them perfectly, one by one. She said Kenneth and I always end up throwing them on. When she was finished, the tree glistened in the soft light. I just wanted to sit and look at it by myself.

Every family I knew in our little West Texas town on the Edwards Plateau, which lies just beyond the Texas Hill Country, had cedar for their Christmas tree. It was almost an annual ritual for locals to go out into the surrounding hills to find the best tree to take home for Christmas. There was no shortage of cedar trees there. Ranchers were more than happy to have them cut. They said there was already too much cedar and too little grass for their livestock. Cedar trees used a lot of groundwater, they said, and grass could not grow without water. The day we went out to find our tree, I had to walk fast to keep up with Daddy and Kenneth. But we finally found a good one. They chopped it down with an axe and dragged it back to the car. Once home, they nailed two boards crosswise onto the cut end of the trunk and placed two wedges under the bottom, one nailed at each end to balance it. Soon it was standing tall in our living room, emitting its fragrant odor that only fresh cedar has. It was a scent I remembered from last Christmas. Years later this same smell, perhaps coming from an old cedar chest just opened, or cedar-lined closet, would take me back in my memories to an early Texas Christmas.

Mistletoe was another Texas memory very special in my childhood. This beautiful mistletoe, which is a parasitic plant, grows on the limbs of the mesquite tree. We had almost as many mesquite trees as we had cedar. Mistletoe stands out in winter as beautiful bunches of Christmas greenery with its dainty waxy-white berries sparkling against its foliage. Eventually this parasitic plant will kill the tree, but perhaps this is nature’s way. Entrepreneurs have specially treated mistletoe which they harvest early in the fall or summer and ship nationwide for others to enjoy during the holidays. We hung ours in a tall doorway which everybody had to pass through when they came to our home. We screamed with delight when someone was caught under it and received a good kiss! No escaping! A good start was my brother who hated to be kissed. Of course, some girls made a point of standing beneath a bunch of it, hoping to be kissed.

Christmas was literally ‘in the air’ now. Mother and Gertrude had been baking all day and the delicious odor of Christmas cookies along with the pungent scent of cedar was almost overwhelming. Tomorrow we would have the turkey in the oven. The ham was ready to warm up; it had been cooked with whole cloves, brown sugar and pineapple slices covering it on the outside. Mincemeat pie was already baked, scalloped potatoes ready to bake, sautéed almonds and salted pecans were ready. These were a few of those wondrous items on our family menu. Mother made the fruitcakes in early November and checked them quite often all month to make sure they remained moist. They were still tightly wrapped in wine-soaked strips of old dishcloths.

I’d waited so long for Christmas to come; I could hardly believe it was here. I wanted to put my presents under the tree right away. Mother took me to the variety story the week before to do my Christmas shopping. I had never done that before. It was such fun! It was the first time I had bought any of the family’s gifts with my own money.

I earned Christmas money by doing chores such as raking the chicken yard, feeding the chickens and bringing in the eggs. Occasionally Kenneth helped me. We had a lot of fun. Sometimes I helped him carry firewood and sweep the sidewalks. We both refused to get eggs out from under the old ‘setting’ hen though. She would try to peck at us because she was protecting her eggs which she wanted to hatch. Mother usually took over that chore for us since we both were afraid. She said the eggs were infertile and wouldn’t hatch anyway because Daddy had killed the old rooster. My first lesson in sex! Why had Daddy killed it? To eat, yet, but also because Mother didn’t want to have more baby chicks right now. It was too cold in winter to raise them. She said that since we sold our extra eggs to customers, she wanted to be sure they were not fertile from the old rooster, for that would ruin the eggs for cooking. I remembered the day I thought the rooster was hurting one of the hens by jumping on its back and pecking her behind the neck, but Mother said, “No, he’s not hurting her. It’s the way chickens mate.” Daddy added that he also crowed way too much too early in the morning when it was still dark. He was getting mean, as well. Sometimes he would flap his wings and start to chase us. I was worried he had to be killed but glad I didn’t have to worry about him chasing us anymore.

Children raised during the 1930’s in the country and small towns learned to take a lot of things for granted, like killing animals for food, raising crops at home in vegetable gardens, canning what one couldn’t save or eat, and shooting wild turkeys for Thanksgiving and Christmas. The old rooster became chicken soup. When it was time to kill a chicken, I would turn away until I was sure the chicken or turkey was dead, usually sticking my fingers in my ears so as not to hear it too clearly and squeezing my eyes shut the whole time. When I heard the thud of the axe, I’d look up and there it would be, flopping all over the place without a head! Blood would be on the log and dirt. I could never understand why a dead chicken kept jumping around after it was dead. Daddy said it had to do with the nervous system. I was fascinated. Somehow, I never felt remorse watching a dead chicken do that, but turkeys were somehow different. I couldn’t watch at all. They seemed more special.

Probably in today’s world with its fancy packaging of meats and poultry, and sterile butcher shops behind glass windows in supermarkets, the average person or child in the United States doesn’t know or care where it comes from. Few ever see the live sources of our food supplies except perhaps in a nursery book aimed at toddlers, with moo cows, baa baa black sheep, oinking pigs, and roosters that cock-a-doodle, which they all love, especially with sound effects. Pictorials and television specials of idyllic farm life are sometimes delightful opportunities to observe farms and country life but sometimes too perfect. Compared to common practices today, where chickens are raised on enormous poultry farms in overcrowded conditions, feet that never touch the ground, round the clock artificial lighting, the TV rendition may not be realistic much longer.

Nineteen-thirties’ chickens, by contrast, enjoyed a more pleasant and happy life, though somewhat limited, outdoors all day in the sun, scratching the soil for bugs and gravel needed to digest their food. They had ample grain in their diets and a safe place to roost at night. Almost everyone had a small chickenyard behind their house. Some had milk cows or a nanny goat for milk. Yet, those were unhurried days by comparison. Life was simple and cherished by those who remember it. And lots of hard work, but children don’t remember that part.

Daddy ordered a new crop of baby chickens in the spring which were brought up from the city by the freight train that came to town every day. The man at the depot called Daddy to come and get our chicks. That was exciting! A trip with him to the depot usually meant I got a close-up view of the big steam engine. Just to walk past it made me feel smaller. It was so powerful and big as it puffed steam like a giant dragon. The engineer blew his whistle which meant it was loaded and ready to pull out. The daily train also picked up huge bags of wool and mohair which had been sheared from Angora goats and Rambouillet sheep from ranches in the area. This was taken to mills to be woven into blankets and other woolen items. I waved as the train laboriously gathered speed and puffed away down the tracks. I waved at the man in the caboose until it disappeared.

We kept the baby chicks in the house near the kitchen on the enclosed back porch with a light bulb placed in the big cardboard container to keep them warm. The container had little holes on the sides, big enough for the chicks to poke their heads through to eat mash which was the baby food for the chick. Mother let me take them out to hold one at a time. They were soft and I liked to hold one up to my ear and listen to it peep and feel its fuzzy yellow head next to my cheek. As they grew larger, we moved them to a special fenced area outside that had a little brooding house to protect them from cold nights and danger from lurking foxes, skunks, and opossums, even nighthawks.

We added a few more ornaments to the tree. Kenneth made one in his grammar school art class, and I made one out of an old empty green wooden spool from mother’s sewing box. She gave me a red ribbon to put through the hole, so I could make a loop with it to hang on the tree. She printed ‘X-MAS 1932’ on it, and I printed my initials.

Now that the tree was all decorated and a white sheet covered the base, I could put those gifts I had bought for everybody under it. I hoped Gertrude would like hers. I had searched the store to find something for her. Mother suggested that since my sister had naturally curly hair, she might like a headband to keep her curls in place. I liked that idea and found one with a pretty red velvet bow attached. I knew it would look pretty in her beautiful hair. I couldn’t wait to see it holding back her short curls.

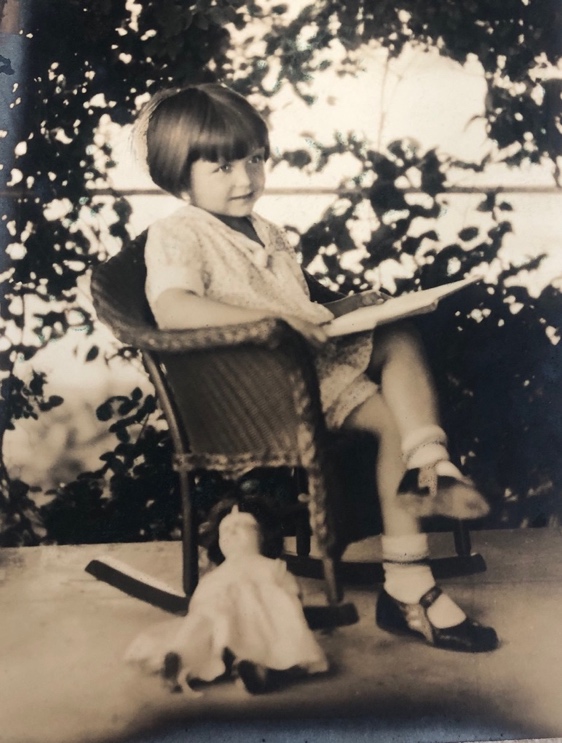

I had what was called a Buster Brown haircut with bangs cut straight across my forehead and my hair was bobbed all around with just the tips of my earlobes showing. It was shingled up the nape of my neck and it felt good to reach back and rub my fingers over it. Most little girls with straight hair wore it like that. On special occasions Mother would either tie a ribbon around my neck or stick a bobby pin through a bow and pin it to one side. We all dreamed of looking like Shirley Temple and curls were definitely ‘in’, but Mother didn’t approve of permanent waves. She said I had to be happy with my hair the way it was, that God knew what was best for me and would have given me curls if He thought I needed them. It bothered me at first, until I saw one of those electric permanent wave machines, when I got my hair cut. It had electric wires that hung down with curling rods attached at the ends. Somebody was under one and she looked like she was attached to it by her hair. It smelled like it was burning which was awful! I couldn’t wait to leave. Mother was right.

The presents I bought all came from the Variety Store, a ‘five and dime’. I found a pocketknife for Kenneth. Mother said he needed one for Boy Scouts. I carried the money in my own tiny pocketbook. Mother counted it for me. I had $1.70. It took a long time to save that much. That was a lot of money to carry around since it was all in change.

One day Daddy brought me a miniature bank from the bank downtown. It had slots for different sizes of coins and was shiny, like silver. Sometimes Daddy added a few pennies or a nickel. He told me if I started saving now, a few cents at a time and got in the habit, I might use that money to help me go to college. He said he would open a savings account for me someday in the bank. He told the same to Kenneth. I knew I never wanted to leave home like Gertrude did. I didn’t want her to go away again. I certainly didn’t want Kenneth to leave when he was old enough to go to college.

Once a man Daddy knew asked him why his daughter was going away to college when she ought to stay home and find a husband and have some grandchildren for him and Mother to enjoy. “They get too damn many new-fangled ideas goin’ off thataway,” he said. I didn’t like to hear him talk about Gertrude that way. I knew she wanted to become an artist and learn to paint real pictures like we saw in the museum once in the city. I didn’t like that bad word either. At our house the worst word I ever heard Mother say was, “Oh, pshaw,” which I didn’t think was so bad! An occasional ‘darn’ would slip from Daddy’s mouth which I pretended not to hear. Mother said slang was used by people with poor vocabularies. I wasn’t sure what she meant, but though it sounded like a pretty good reason not to swear. She also told me in the Bible it said not to swear.

Later that day Mother brought me a cookie she had just baked with a glass of milk. She said the gingerbread men would soon be ready to frost if I wanted to help. “Yes, I wanted to put in the raisins for eyes and buttons, please!” I answered, “But, first I want to put the gifts under the tree that I bought.”

I hoped Daddy would like what I chose for him. I bought him some pretty white handkerchiefs to wear in his coat pocket when he went to church, and some he could use for every day. Everybody carried handkerchiefs, women and children, too. Paper tissues were barely invented and “too expensive,” Mother said. She admonished me not to blow my nose on a ‘good’ handkerchief and never to do it in public or at the table, “and certainly never on a lace handkerchief”.

That same day at the store, I chose a box of pretty blue stationery with a design at the bottom with envelopes to match. I thought Mother would like that because she wrote letters to her family. She also wrote to friends whom she said she missed. “This way they won’t forget me”, she said. Sometimes Mother read their letters to us if she thought we would be interested in them. There was one friend in particular who had become a missionary in a far-off country called Burma. When she read those, it was like a storybook. Mother had a younger brother who had joined the army during the Great War (World War I). After the war he stayed in the army, became an officer and traveled to faraway place like the Philippines. My first lessons in geography began with his letters and postcards and those from Mother’s friend in Burma.

I put the gifts around the tree when no one was looking. I noticed several more gifts had been added. My name was on one! I was tempted to squeeze it, but thought better of it. Something else caught my eye. It was a big box that had come in the mail the week before and was still wrapped in brown paper. I wondered who it was from. Maybe Daddy forgot to open it, but why did he put it under the tree?

After supper on Christmas Eve we gathered around the piano to sing Christmas carols. Gertrude played the piano. I didn’t know all the words but had learned some Christmas songs in kindergarten and in Sunday school. We sang a lot at our house, and I couldn’t wait to learn to play the piano like Gertrude. Mother told me that I would be able to take piano lessons when I was a little older. A new piano teacher was coming to town next year and since rooms were hard to find, Mother offered our ‘extra room’, which was really Gertrude’s, who would be away at college. Her ‘rent’ would be piano lessons for Kenneth and me! Gertrude said that was OK with her. She would sleep with me when she came home for an occasional visit, but she said she’d still want her room back for summer vacation.

After singing carols we sat around the Christmas tree for a while talking. I wondered if Santa’s sleigh was already flying around the world. What country would he go to first? My mind was full of questions. How could he put all the gifts in one sleigh? Since there was no snow, could he land on the ground? How could he come down the chimney if he is so fat? Won’t he get burned by the fire? No one else seemed concerned about it. My brother finally said, “He’ll find a way. It’s magic.” That satisfied me for a time. Daddy interrupted, “Mother and I have decided to open the Christmas box from Grandpa and Grandma tonight. Would you like to do that since it’s Christmas Eve?” he asked. He reached to get the big box out from under the tree. It was the one I had seen earlier.

Our grandparents lived in another state, too far for us to travel to see them in the winter. I clapped my hands in excitement. I remembered we had mailed their package several weeks earlier. My parents packed things that were needed and some goodies, too. Daddy sent them shelled pecans from our trees. Mother put in a small fruitcake she had baked and also homemade sugar cookies and Christmas candy. Daddy made napkin rings out of wood. Mother made some green napkins to use with them. She also sent a sweater she knitted for Grandma and a warm vest for Grandpa. In those days most Christmas gifts were homemade. Mother said they were more meaningful than store bought goods. She had been sewing in her bedroom a lot lately, making gifts for the family. Daddy was working on something in the garage for Mother which later turned out to be a beautiful wooden flower stand for the living room. She loved house plants. Kenneth wasn’t telling what he made for me (it was a little bow and arrow he made at Boy Scouts). I was the only one who hadn’t made my gifts. I usually made something in kindergarten to give for birthdays or would draw a picture. I could still draw a picture for everybody. Gertrude showed me a picture she had painted for Mother and Daddy while she was studying art in college. She warned me not to tell. I wondered if she had painted one for my room.

Daddy got out his pocketknife and cut the twine, which was tied around the box, then he slit the paper. While he did this, he reminded us that anything they might give us was sent with love and sacrifice, for times were hard and Grandpa could no longer work. We were told about the many children in the world, and even some in our town, who would be without gifts this Christmas. Some had no shoes and others were without warm coats. Many had little food. He reminded us of the bad depression which meant people lost their jobs and homes. It meant little to me since we always had enough to eat and a warm house to live in, but I knew Mother fed poor people whom we called tramps. They came to our back door daily. Daddy always gave them a job to do in exchange for a meal, which they ate on the back porch. Mother wondered why they always came to our house. Daddy said they had ways to let others know where they could find food and small jobs as they made their way to California. Our church collected toys and outgrown coats and shoes for the poor children in our town. Mother let me choose which toys I wanted to give, and I knew she gave away all my outgrown clothes.

Finally, the box was open and inside was a bag of black walnuts, my mother’s favorite. They didn’t grow in Texas. Mother said the shells are very hard to crack, much harder than pecans, but she really appreciated them. I thought pecans tasted a lot better.

There was a gift for everyone. Grandma sent hand crocheted doilies for Mother and Gertrude. There were three other small packages for Gertrude, Kenneth and me. Mother suggested we open the other gifts first. We watched each other as was our custom. Again, Mother reminded us of hard times by saying our grandparents shouldn’t have sent so much this year. My turn finally came. I opened my present with great anticipation. It felt like a book. I liked to have stories read to me, but I would soon learn to read in first grade. I unwrapped it. It was a book! Gertrude read the title, “The Sweetest Stories Ever Told”. It was about Jesus. Every page had a colored picture. When I turned the pages, I recognized some of the pictures and stories we had in Sunday school. As I turned the pages slowly, I saw a real scary picture on the next page and quickly closed the book. It was a terrible picture of Jesus! It looked like one I had seen in church, a stained-glass window, but I tried never to look at it. Jesus was on the cross with blood dripping down all over his face. There were thorns on his head, and he looked so sad. Why did Grandma send this to me? I decided she had not looked at all the pictures. She wrote inside the cover, “To the sweetest little girl in the world,” and “May this book keep you from sin.” “What did that mean?” I wondered aloud. “What is sin?” Gertrude said she would explain later. I just wanted to see pretty pictures of little baby Jesus with his mother and daddy, Mary and Joseph, like in Sunday school.

Daddy was still passing out gifts. There was a pretty brooch for Mother. She said it was one that Grandma had saved for her which had been in the family a long time. They sent Daddy a pretty new tie with a tie clasp. Kenneth got a new bag of marbles. Gertrude’s gift was a silver Indian bracelet that real Indians had made. It had turquoise in it. Grandma had bought it from Hopi Indians.

Mother said how thoughtful and generous they had been, and that we must each remember to write a nice thank you letter. I didn’t know how to write yet, but I could print some of the letters of the alphabet and my name. I would draw a picture and ask Mother to write on the back for me, but I was never going to open that Jesus book again! I wouldn’t tell Grandma. I wanted to look at all the other pictures and hear the stories but was too afraid I might see the scary picture again. Daddy gave us the other gifts. Mine felt bulky and heavy. I wondered what it could be. Carefully, I untied the ribbon and there, wrapped in white tissue paper was a little velvet bag with a drawstring. I pulled it open and dumped the contents of it into my lap. It was money! Lots of nickels, dimes and pennies! Daddy counted it all out for me as he stacked the coins into little piles. When he was finished, he told me I had a whole dollar! That was almost as much as I earned doing chores.

Kenneth opened his and found a real silver dollar dated 1885, the year Daddy was born. Gertrude had one, also dated 1885, the year Mother was born, too. I had never seen a silver dollar before, but Daddy said in the northwestern states, people used them instead of dollar bills. I didn’t mind not getting one, for I had lots of money to jingle, waiting to be spent. Daddy must have read my thoughts. “Let’s get your bank out so you can save part of it,” he suggested. Then Mother said I might want to keep out a nickel to put in the Sunday school collection plate. I noticed they didn’t say that to Kenneth and Gertrude because they already had said they would never spend their dollars! Well, I would do what Mother and Daddy said, but I was going to spend all the rest. In my mind I had already spent it.

When we shopped for Christmas gifts at the Variety Store, I saw a little red dump truck I wanted so much but knew I couldn’t buy anything for myself, at least not while I was Christmas shopping. Anyway, I didn’t have enough money. I really wanted that red truck because I loved to play in the big sand pile Daddy kept handy for various projects. I couldn’t ask Santa to bring me two things, so I had asked only for the doll. I had never had a real dump truck of my own. This was my secret now, and I would draw a picture of it, or get Gertrude to draw it for me when I ‘wrote’ Grandma and Grandpa. I knew Grandpa wanted me to buy whatever I wanted. Grandpa’s are like that. He was very old, and I didn’t get to see him often, or Grandma either. I hoped they could come to see us this year. Daddy said we might be able to drive there next summer.

I fell asleep quickly on Christmas Eve. Thoughts of Baby Jesus in the Manger, the Three Kings with gifts, and the bright Star of Bethlehem took scary thoughts out of my head, like the scary picture in my new Jesus book. Also, visions of the little Red Truck helped. I remembered to ask God to send Santa Claus to all those poor children’s houses that Daddy had told us about and thanked Him for choosing my family for me when I was a baby up in Heaven. Then I heard the faint jingle of sleigh bells. I wanted to go outside to look but was too sleepy. Santa must have been very high in the dark sky on that cold Christmas Eve.

The End

Dreaming of Christmas Magic