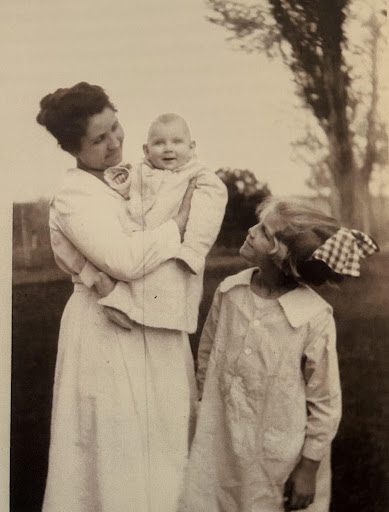

In November of 1914 the Orville, Edith and baby Gertrude returned to Colorado. "Hoping to take over a farm and so my wife and I stayed there quite a while. My family’s farm or her farm. It had 160 acres; raised lots of beets, apples, but mostly hay. As time went on, we decided we didn’t want the farm because it had too many drills in it; two one way and two the other. That meant a lot of hard plowing, hard irrigating, and extra hard work and, in addition, the best part of the farm became ruined by alkali water seeping through the soil on a wide hill having some fifty odd acres. So, I decided I was going to get back in my field in 1915.” O.G.B.

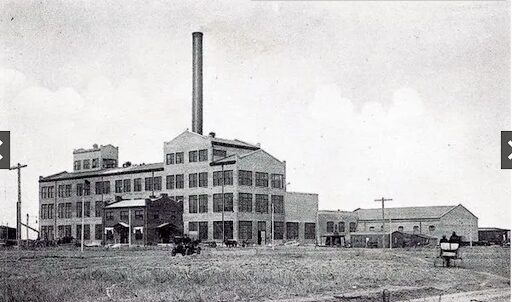

As a result of the decision not to take over the farm, Orville accepted a job at the sugar beet factory in Longmont. Initially, it was experimenting with new ideas of harvesting beets. Orville and Edith stayed here until February 4th of 1915. “When these tests played out, I was given a job inside the sugar mill. It was pushing the shredded beets around and in filling the big vat. Finally, the head boss of the entire centrifuges took me over. Here I worked out the rest of the campaign.” O.G.B.

By April of 1915 they had moved to Denver, where Orville worked on cyanide fumigation for the human bed bug in rooming houses. He also did considerable work in insecticide manufacturing of lime-sulfur. He completed this work in August of 1915.

In September of 1915 he worked on a stock ranch in Yampa, located in northwest Colorado. “Here I had to walk a half mile to milk a couple of cows. The warm milk was used on hominy grits; breakfast food.” It was during this time Orville learned to ride a motorcycle which he rode frequently from place to place.

From October to January, Orville was employed by Great Western Sugar Factory. His task was to work on the efficiency of experimental beet harvesting machines, primarily increasing the percentage of six of the sugar beet topping machinery, and other experimental work that other people had invented. He also worked inside the sugar beet factory. “It was plain, hard work, but all of it responsible work, and as the saying goes ‘Anything that moves is dangerous.’ Well, there’s a lot of danger all through the factory even though it’s built for safety.” He worked through the factory as presses, thick syrup, cells and finally a brown sugar cutter.

Orville recalls seeing one man, working on the machine, fall asleep and subsequently get killed. “He had a crowbar there. I think he went to sleep as he stuck that thing in there. And of course, that hit that cover on the inside which was steel frame. Well of course he was gone in an instant. It just cut him in two with the crowbar. It was the only death I’d seen in a factory.”

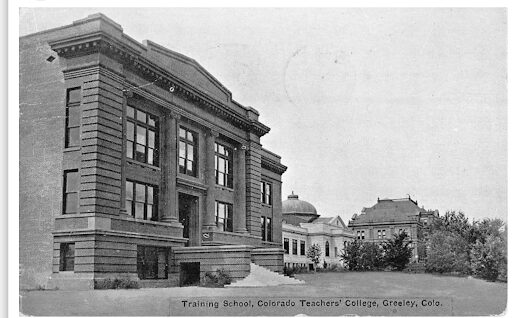

From March to May of 1916, Orville studied at the State Teachers College in Greeley, Colorado taking zoology (bird study), biology (advanced biotics), education, school, Psy4 and Psy 6 for twelve weeks, earning nineteen credit hours. J.H. Hays was the acting President.

In June and July, he studied at Colorado Agricultural College for six weeks earning 10 credit hours and then in August he worked there in the Experiment Station as a helper under George M. List coddling moth investigations in the Grand Valley in Grand Junction, Colorado.

In November of 1916 to February of 1917, Orville worked for the Holly Sugar Company in Grand Junction as a sugar chemist. “This factory had been operating at a loss, so an expert sugar chemist was hired. Being a new chemist, I had to familiarize myself with all operations in the chemical laboratory, strictly a sugar laboratory, and the entire factory is based upon the findings in this laboratory. So, the chemist is a big man for the whole factory. My work was to analyze samples from all over the factory and records were made and kept. At first the sugar tests showed in several places that too much sugar was getting by. Here is where the head chemist got busy and forced corrections. He made from 10/100 % to 8/100% of sugar. Further changes brought the waste sugar down to 5/100 or 6/100% sugar.” O.G.B.

“My job the entire campaign was to analyze sugar. They have a little sample boy. He takes samples of the sugar; beet pulp, cooked pulp, steamed pulp, lime presses, Sulphur tanks, centrifugal sugar, brown and white sugar, anything throughout the entire factory, and brings it into the chemical laboratory. Then we run the analyses every hour using the cyclometer. When the boss in the place comes in, he looks over our records because we make a record every hour. He goes over that and if something is not up to par, he knows right where to go to put his finger on the trouble. In the later stages, all of the unusable sugar is fed with beet pulp to the cattle as feed.”

In March Orville did ranch work near the eastern slope of the LaSalle Mountains. From April 1st to April 15th, he worked in a plant manufacturing lead arsenate (an inorganic insecticide used primarily against the potato beetle) in Grand Junction, Colorado.

From April 15th to October 15th in 1917 Orville was employed as a canal rider and supervisor of ten to fourteen miles of the main canal, part of the Grand Valley Project of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. His duties included distribution of water to the consumer which were primarily the fruit farmers and crop farmers. The canal was part of the Grand Valley Diversion Dam built between 1913 and 1916 which diverts water into the Government Highline Canal for irrigation in western Colorado’s Grand Valley. The distribution was by acre foot, estimation of evaporation and seepage of lateral water, control of flood gates on the main canal and giving helpful information to the water user where advisable. This work was under the United States Reclamation Service.

I was a ditch-watcher you’d call it. I had to keep records, but that wasn’t any trouble for me at all and I was permitted a Cipolleti Weir (an overflow structure that is used to alter flow characteristics). That’s the way they measure water by the second foot. So many second foot of water per minute that’ll go over the weir in a second of time or a minute of time. The government had gates and they had padlocked for all the farmers. My job was to deliver the amount of water that they wanted whether it was a quarter of a second foot or a half a second foot, or whatever it might be. North of Grand Junction that’s where the canal was, up on the prairie north.” O.G.B.

“That was all farmland there and homestead land in there as well above the well where people could live above the roaring water. This line went in way above that and took in a bit of area of land that was never irrigated before. Those canals would be about twenty-foot-wide and six foot deep. Course by the time they let it out different collaterals, we called them, why there would be water clear down to the end.”

“There was one lateral that I had that was seven miles long. So, I’d have to give out to people up in the upper end, and come way down here seven miles, and then meet my water coming down that I turned up by the canal.”

“Coincidentally why I took advantage of my knowledge of entomology, and I could answer a good many questions talking to different farmers and so on.”

In 1917 or 1918 Orville began work for the U.S. Bureau of Entomology and later ‘Seven Plant Quarantine’ in Washington, D.C. From October 16th, 1917, to July 1922, Orville was a Special Field Agent for the Bureau.

On November 1st, 1918, their second child, Kenneth Knoll Babcock, was born in Dallas, Texas.

Note: On August 20, 1912, Congress passed the Plant Quarantine Act. The legislation provided for the establishment of the Federal Horticultural Board, composed of two representatives from the Bureau of Entomology, two from the Bureau of Plant Industry, and one from the Forest Service. The task of the Board would be to design and manage an import inspection system and make recommendations to the Secretary of Agriculture on the designation of quarantines and eradication measures. Initially, the Act specified that inspection of imported goods should be conducted by state employees (with no federal funding) but coordinated by the Horticultural Board. This system was not uniformly carried out among states and responsibility for inspection was later made a federal responsibility.

For further information see “The Legacy of Charles Marlatt and Efforts to Limit Plant Pest Invasions” by Andrew Liebhold and Robert Griffin, American Entomologist, Volume 62 Number 4.