Orville worked at College Park, Maryland at the Agriculture Experiment Station from September 1910 until April 1912. Professor T.B. Symonds was in charge. He taught plant histology, microscopy of food and drugs, nursery, foreign importation plant inspection, orchard inspection, and economic work on the peach lecanium and San Jose scale.

Invariably, Orville was always chosen as the person to go out on calls to nurseries and orchards to settle disputes between neighbors and spraying; one would complain about the other one and send it in to headquarters. “So finally, I was sent out to this particular orchard, and this man here just raising Cain that he had to run his little nursery. His neighbors were just next to him. Well, he wouldn’t spray his stuff, but the nursery sprayed his and he did complain.”

“Well, Dr. Simmons, at the college, was up against it. He was the head man. He’d have to have the sprayed with all the complaint. He fiddled along afraid he wasn’t going to do it. Finally, I was sent out there to investigate that there and do whatever was necessary.”

“Well, this was the only time I ever did anything of the sort, but I went out there, and when I come up to the owner of the place, he was working on something. I told him what my business was, he grabbed a fork and wanged (to hit hard) it down on the ground, and he just come out and told me what he thought of the man down at headquarters, and went on for a little bit, and cussed a while.”

“Then he looks at me and says, ‘You’re not to blame for this. You have to do this. You’re sent out here to do it.’ The fellow next door was forcing him to get all that stuff sprayed.”

“After he cooled off a little while, I tried to talk to him, to smooth things over and see what he could get around. Well, we couldn’t get anything out of it. He wasn’t going to do it, that’s all there was to it. Well, I told him, I have to do something, and I’d rather do it peacefully.”

“Nope, he just wouldn’t have anything to do with it. Well, finally I saw what I was up against. I knew what the law was. So, I walked on back to town, wasn’t far, and went to the sheriff, and he took me to the lawyer there for our work. He looked up the law in regard to that kind of work I was doing and found out what the law was there.”

“There was only one thing I could do and that was to go ahead and inspect it. He said, “Now I’ll send the sheriff up there with you and when you get there, you follow instructions of the sheriff, whatever he says.”

“So, we went up there. Got back to the place, here come. He saw this sheriff coming along with me, you know, so he knew what was up. When we got up there, he spoke to him. He said, “Now what’ve all this trouble about?” So, I told him, and he says, “Now you got your information, you’re sent out there to inspect this place, and now go down and inspect this—everything here.” That meant raspberries, blackberries, apples, all the things that the San Jose scale can be found on. So, I went on. I had a job that time.”.

“When I got through, I told the farmer, I’m sorry to mention, but your San Jose scale is awful heavy on your gooseberries and raspberries. Very bad. Not so bad on the apples. So that was all. I went on back and, of course, I sent the report in.”

“Then the war boiled down at the other end, down at the college …cause that meant Dr. Simmons had to take action. The law required the man be forced to spray and to be charged for it. He had to spray the whole place. He was infecting the nursery.”

“Whenever there is trouble it is usually between the people (living next door or nearby) themselves.”

“Unfortunately, I had every darn case like that to follow up. He (Dr. Simmons) would always send me instead of someone else.”

“The east coast of Maryland was very appealing to me for here were the beautiful holly trees and cypress growing in the water, all had widened bases. Six other trees of Maryland were the chestnut tree, Naline persimmons with small fruits but best eaten after the frost. Apple orchards and peach orchards were everywhere. Patches of buckwheat was growing everywhere. One of the most interested plants found was the skunk cabbage growing by the water’s edge. Of course, I examined it. It was well advertised, skunk cabbage. On the streets in Baltimore, Maryland one can find many mature men who were roasting chestnuts and selling them by the handful. They were always placed in the coat pocket. When properly roasted they were excellent eating.”

Riverdale, The Calvert Mansion. The history of Riverdale Park begins not with the town itself, but with one of Maryland's founding families. In 1801, Henry Joseph Stier, a Belgian aristocrat, established his plantation on a large tract of land north of Bladensburg. Stier planned the house in 1801 to resemble his Belgian residence, the Chateau du Mick. Four years later, Stier returned to Belgium, leaving the unfinished Riversdale to be completed by his daughter, Rosalie Stier Calvert, and her husband, George Calvert. In the summer of 1803 Rosalie Stier Calvert and her husband moved into the recently constructed mansion on this estate, which they called Riversdale Manor. The original boundaries of the property comprised 739 acres, and the slave plantation grew to nearly 2,000 acres by the middle of the nineteenth century. It was roughly bounded, in modern terms, by US Highway 1 on the west, Kenilworth Avenue on the east, Paint Branch on the north, and the Town of Bladensburg on the south. When Riversdale was first constructed, the old Baltimore Turnpike ran through the western portion of the property. This became what is now known as US Highway 1. In March 1833, the state's first railroad, the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O), was chartered. The Washington, D.C. to Baltimore line was first used for passenger traffic in August 1835. These transportation corridors are important features of the modern town of Riverdale Park.

Rosalie and George Calvert's son, Charles Benedict Calvert, established the Maryland Agricultural College in 1856, the first agricultural research college in America, on part of the Riversdale property. It is now known as the University of Maryland, College Park. In 1887 Charles Benedict Calvert sold the Riversdale Mansion and 475 acres to a group of New York real estate investors. The Calvert family farmlands became the site of the future town of Riverdale Park, and the mansion itself has served as the offices of the town developer, the home of senators, and eventually as M-NCPPC office space. After decades of heavy use, Riversdale Mansion fell into disrepair by the late 1960s. The Riverdale Historical Society spearheaded the mansion's restoration. This work began in 1990, and the mansion was restored and reopened to the public in 1993. Today, Riversdale is recognized as a valuable and unique source of identity and a focal point of the town.

Beginnings of the Town: 1889–1920. The end of the Calvert family's tenure at Riversdale allowed for the creation of the subdivision of Riverdale Park. The town itself became a desirable residential community because of two important factors; its proximity to Washington, D.C., and the advent of passenger rail service to suburban communities at the turn of the century. After the Civil War, a number of unplanned speculative settlements and platted subdivisions developed in the county adjacent to these railroad lines and junctions. The new passenger rail lines allowed the county's residents to commute to Washington, D.C. and Baltimore. The first lots were platted in 1889 by surveyor D. J. Howell, with the key feature of the subdivision being the B&O Railroad station. The major streets near that area were designed to converge on an ornamental town center that incorporated the semicircular design of New York Place (now Natoli Place). The early streets were laid out in a grid pattern, straddling the rail station, and ending at the Baltimore Turnpike. Baroque elements of this plan included park spaces, green circles with diagonal cross streets, and vistas terminating at the Riversdale Mansion. The original streets were named for Presidents Washington through McKinley, as well as for other distinguished statesmen such as Clay, Lafayette, and Beale. This homage to the Federal City underscored how the livelihood and identity of the town were inextricably linked to the nearby capital. Most of the original building lots had 60 feet of frontage and were about 150 feet deep. To the northwest, lots had smaller dimensions to accommodate a diversity of incomes. The Riverdale Park Company built the first model houses in the subdivision in order to entice development to the area. The Harry Smith home at 4707 Oliver Street and the Wernek House at 4606 Queensbury Road are two of these models. Both are examples of a substantial style of dwelling designed to convince potential lot purchasers, builders, realtors, and investors that Riverdale Park was ‘the most picturesque suburb of Washington.' The Riverdale Park Company built these model houses and the original Victorian B&O Railroad station in the early 1890s.

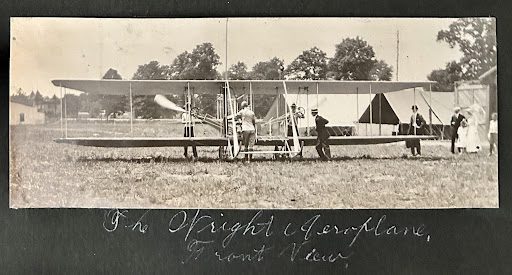

The Wright Brothers and College Park Airport

After making the first sustained, controlled flight of a heavier-than-air vehicle in 1903, Orville and Wilbur Wright made repeated attempts to negotiate a contract with the U.S. Department of War. The military men, at first, were slow to grasp the battlefield applications of airplanes.

College Park Airport began as the training site for the first military pilots in the U. S. Army. It is located about two miles from the University of Maryland. On August 1, 1907, the Army's Chief Signal Officer established an Aeronautical Division in his office and contracted with the Wright brothers to build a flying machine, which was delivered to Fort Myer, Virginia, in August 1908. The contract required flights to demonstrate performance and flying training for two Army officers. Orville Wright circled Fort Myer's parade ground in Signal Corps Airplane No. 1, the first military airplane in the world, but he was seriously injured when the plane crashed. Delivery of the airplane and training of the Army pilots had to be postponed until 1909.

After those early test flights, it was determined that a facility specifically designed for aircraft was needed. By that time, the Signal Corps has leased a field in College Park, selected by Lt. Frank Lahm based on observations during a balloon flight, and built a small hangar for the airplane. Wilbur Wright oversaw the construction of the College Park Airport in 1909.

On October 8, 1909, Wilbur Wright began flying training for Lt. Lahm and 2nd Lt. Frederic E. Humphreys. Lahm and Humphreys became the first official military pilots.

Wilbur made 55 flights at College Park, including his last record-setting flight, 46 miles per hour over a 500-meter course. His final flight on November 2 was the last time he ever flew in public and also one of his last flights as a pilot. In 1911, civilians began flying airplanes from College Park Airport.