Written several years after the family returned from South Africa and had moved to Champaign, Illinois. (1960’s)

As I was methodically going through the motions of unpacking and setting up housekeeping, my mind was busily engaged in planning where to put all of our things, as well as the furniture arrangement in the beautiful seventy-year-old Victorian mansion we had just leased.

Although it had seemed a delightful challenge at first, the mess and disorder of the moment was discouraging. Despite the house’s glamorous name, Windy Gates, which was scrawled in wrought iron on the double gates leading into the garden’s circular drive, the lovely old house was going to take some sprucing up if it was to regain its original beauty and charm.

Our landlady had told us that it was one of the oldest homes in Johannesburg, South Africa. The house, with its twelve-foot-high ceilinged room, was more than large enough for our family of five and my parents, who had returned with us to visit South Africa after our long leave in the United States. The children delighted in hiding in and exploring the many rooms and found many secret hiding places not likely to be found in modern homes, such as a walk-in attic, a large pantry, a flower arranging room, a large laundry chute on either side of an enormous walk-in linen closet and a real secret panel in the walnut paneled den, which contained a safe and was large enough to hide in. To them it was a rich combination of setting from a Nancy Drew mystery and Jane Eyre. We were fascinated with Windy Gates as well. I soon found myself weaving stories about the original owners as I unpacked. Attacking the last packing box of china, I was startled to hear a voice from behind penetrate the busy silence!

“Good Morning, Madam.” I turned quickly. Half leaning on the open kitchen door was an African, fingering his sweat-stained hat.

“What do you want?” I asked, not really liking him being there at all. He replied that he had heard we were looking for a ‘boy’.

“Is your passbook in order?” I asked. His face looked strained. The wretched passbook. The hated symbol of no integrity, no rights. A number. A mug shot. Head up, unsmiling, indented with the government stamp.

He replied, “No, Madam.”

Even I, a foreigner, knew it was against the law in South Africa to hire a ‘native’ whose reference book was not in order. I was about to send him on his way when my husband came into the kitchen carrying a large crate. As he awkwardly started to set it down, the “boy” ran forward, dropping his hat to help him. Not waiting to be thanked, he backed to the door again, retrieved his hat and said, “Good Morning, Master. I have come looking for work. I know this house, sir. I can help you.”

He talked freely, but with obvious respect for the “Master.” I heard him identify himself as Lewis, pronouncing it Lew-eeees, with the accent on the last syllable. He said he came from Mozambique (Portuguese East Africa), but he had worked in South Africa for a number of years as a houseboy. His pass (reference book) had repeatedly been stolen. It seemed that in the interim a law was passed prohibiting an African ‘native’ other than South African from obtaining a new reference book, making it impossible for him to renew his. Desperate to stay in South Africa (the pay scale and living conditions being much higher in South Africa), he attempted to buy one through illegal channels and finally did (from a white man), for an exorbitant price, only to find he had been cheated and that it was worthless. As he told his story, my mind raced on in parallel. He would be arrested if caught, and anyone hiring a ‘native not holding a legal reference book would be heavily fined. By law we were required to take every African servant we employed to the Government Pass Office to be registered. We also had to sign his pass every week on his day off and pay two shillings a month or two pounds, four shillings ($5.60) a year taxes on him. No sensible person would hire a ‘boy’ illegally. Besides, his case was just one of many. There was nothing we could do about it, so of course we could not consider hiring him. Still, I thought, two extra hands could make a big dent in the job ahead.

Our own two servants of long standing, Grace and Jack, had failed to show up at the new house on the appointed day, though I was sure they would eventually come, which they did. But their not being there when we needed them most had put us in an unfortunate position. In a foreign country there are often so many unaccustomed chores that one needs help from those more familiar with the local customs and problems, such as knowing where to order coal for the slow combustion hot water heater or anthracite for the Aga cook stove and having someone to start both; knowing what can be delivered, such as bread, milk, vegetables and meat; where to buy those things that are not delivered; and how to get the dust bin (garbage) collectors to stop. In South Africa, floors have to be polished daily because the builders do not usually seal the wood. The beautiful hardwood floors, sometimes in exquisite parquetry, are lovely, but demand this constant attention; hence, instead of buying a small one pound can of paste wax every few months as one does in the States, one buys a gallon can about once a month for the houseboy, with his muscular arms to rub in and polish regularly. Despite our desperate need for help, I expected my husband to send Lewis away. Even with pass in order, no one would hire a stranger to work in his house. Personal references had to be checked. As I saw my husband on the brink of decision, I was about to voice my opinion, when our seventeen-month-old son, Walter, toddled in, whining and hungry, tugging on his older sister’s hand.

I realized that I hadn’t even rinsed the dishes or cooking utensils and had no place ready to put them when I did. And, of course, nothing was prepared for lunch. I quickly found a bottle of baby food in an air bag and heated it. Washing his baby spoon, I fed Walter, feeling desperate enough to cry. Perhaps this was the turning point from a negative to a positive decision, but the next thing I knew, those strong ebony hands were taking over where I had left off on the box of china, and I carried Walter from the kitchen to put him to bed and to proceed with the task of unpacking and setting things in order upstairs. And I let the chips fall!

Hearing many stories about servants, I had trained myself to distrust strange ones. I kept this to myself today, however, not wanting to upset our three children or my elderly parents, who had, of course, read of the Mau Mau atrocities occurring around that time, and we had only just persuaded my mother to make the trip. We pointed out that South Africa was over 3,000 miles south of Kenya and was a modern, thriving and beautiful bi-lingual (English – Afrikaans) city with over 1,000,000 population. Still, she had read Alan Paton’s Cry the Beloved Country and had not been easy to convince that all was well there.

Six beds, four closets and fourteen suitcases later, I returned to the kitchen. Where it had been a medley of confusion and disarray, every dish had been washed and put away on clean, paper lined shelves. Empty crates had been removed, the Aga stove was going, and the floor was scrubbed and polished. My husband, Bob, was having a lively conversation with Lewis about Mozambique, each mixing his English and Portuguese to fill in bits of language that the other needed help on. A stranger might have thought that he had worked for us many years.

Though we ate lightly that night, we sat down to a table set with the right number of forks and spoons, a tablecloth, and a small floral centerpiece that had somehow found its way to our table. I later discovered that this was Lewis’ specialty, flowers. We paid him for his day’s work and he departed, but not before he had brought us a tray of steaming hot tea, his own idea and truly appreciated after an exhausting day. He left, saying he would return the next day and was gone before we could discuss this point. With a semblance of order in our lives again, we went to bed.

At six a.m. Lewis was waiting at the kitchen door. Bob discovered him when he went to let the dog out. Could he really turn such willing hands away? Was it better to turn a deaf ear to our acquired South African consciences and fears?

By the time I reached the kitchen, the table was prepared for breakfast and another day began. A more orderly one than the day before. We took time to explain to Lewis, however, that although he had been exceedingly helpful, we already had a houseboy who would surely be arriving at any moment. We also pointed out that our maid of four years would most certainly come today or tomorrow, and, of course we wouldn’t be needing him after that.

Lewis worked quietly and quickly. He wore tennis shoes and his own clean khakis. He seemed to complete each job before we had found another for him to do. By week’s end, Windy Gates glistened, probably cleaner than it had been in years. The tall, narrow windows shone, the floors had been cleaned and brightly polished with fresh, clean wax, the carpet was cleaned and vacuumed. Even the banisters of the tall stairway, grimy with years of hands gliding up and down, was scrubbed and freshly waxed. Old fashioned ceiling lamps had been thoroughly emptied of charred insect remains and washed. Jobs had been done that otherwise wouldn’t have been accomplished for weeks. After only two day’s work, we knew he was too good to lose. Passes be damned! After a week, we knew he was indispensable. There was little doubt that here was a rare gem in that city of gold, Goli, as Johannesburg is affectionately called by the African.

By the time our prodigal servants, Jack and Grace, arrived several days later, Lewis ignored the fact that “we wouldn’t need him after they arrived.” And we didn’t get around to reminding him. He presumed that we most certainly did, and he unobtrusively put himself in charge of the other servants, despite their seniority, showing them what had to be done in the new house. He must have sensed that they would be overwhelmed by the grandiose surrounding. Lewis had worked his way into a permanent place in our home, and later into our hearts, saying little but working big. He didn’t have to talk. His worked talked for him. He wanted to belong to a family. He had chosen us. And before we knew it, we belonged to him, too!

To our dismay, we discovered that the house and two-acre garden were so large that we needed a garden boy. Well, why not relegate Jack to the garden and keep Lewis as the houseboy. The matter was settled. We would definitely take the risk. There was little doubt that Lewis did know this house or had known one very much like it. He must have known all the time that we would need two ‘boys’. Jack was happy with the arrangement. A Zulu from Natal, South Africa, he loved the sun and soil, and after his daily chore of keeping the slow combustion water heater and Aga cook stove going, he kept the garden in full bloom, winter and summer.

Lewis appointed himself butler as well and allowed no one to get to the door before he did, after first peeking through the peephole to make sure it was not the police. Our guests were treated royally. People who had no business bothering Madam and Master were turned away. Children were made to clean their feet and firmly sent to the back door if they were dirty or noisy. They obeyed without question. All who entered were invited to sit and wait while he quietly announced their presence. Our life had suddenly become very formal. Grace had the kitchen, beds, washing, ironing, dusting and, Walter to keep her busy. Lewis had the rest of the house. He soon had it running alike a valuable antique clock, silent, smooth and beautiful.

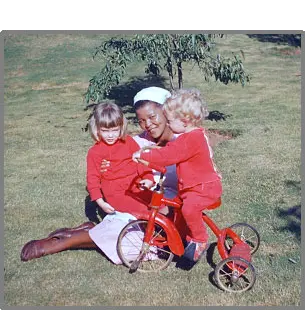

Lewis was training us well. He proudly dressed for dinner in Bob’s old hospital intern suits, which had somehow been saved. He insisted that I buy him white serving gloves. Against the white of his clothes, his skin was ebony black, giving him an air of elegance. He scowled at the children if they dared to arrive for dinner unkept. I could feel his disapproval if I came to eat in Capri pants or a house dress. I always felt ‘anything goes’ for breakfast or luncheon in the breakfast room or sun porch, but not for dinner in this nineteenth-century dining room. Containing its original furniture, the grand old table easily seated twelve without leaves and twenty-four with the three-yard-wide leaves. We put them all in once just to see. The buffet was massive and held as much as I cared to put in it. It even contained a wine cabinet. A fireplace warmed this room during the chilly winter months. The cushioned chairs were of a size befitting the dining room suite, providing plenty of leg room. When they could slip past Lewis’ watchful eyes, the children found the table a perfect playhouse on a rainy day.

Whenever Bob and I dined alone, Lewis still went through the ritual of serving us as formally as if the Queen of England had been present. We simply had no choice in the matter. Sometimes for lunch I would prepare a picnic and eat with the children down in the bottom of the garden under our big old Silver Oak and Jacaranda trees. Lewis would inevitably come running across the green grass, decked out in his white suit, holding a cloth-covered tray and serving us with all the dignity he could muster for such informality.

Perhaps he had captured the actual mood of the house and expected us all to abide by its rules. And certainly, the house had been built with servants in mind for gracious living. Though we had our own furniture, the owner had left Windy Gates partly furnished because of the immensity of the house and also because of the difficulty in moving the large, heavy period pieces. Being such a large house and rather run-down, it needed constant attention. There were always jobs and chores needing to be done to keep it in good order. Also, with small children about, there was the usual disarray that comes with them.

Lewis was the only servant I ever knew who absolutely did not have to be told what, when or how to do anything as far as the house was concerned. Now, anyone who has lived in a foreign country where servants are relatively cheap and plentiful will only too quickly agree that this is indeed a rare trait. In fact, often the most difficult thing about servants and overseas living is being unable to live happily with or without them.

In retrospect, I am sure that Lewis was one of those rare individuals who senses one’s thoughts and needs almost before one does himself. He was well trained. There was little doubt of that. But he quickly adjusted to our way of life, which was of course, different in many ways from the South Africans. Our American customs must have been strange to him. Though he understood some English, our American accent was difficult for him. He gradually overcame these difficulties. Under different circumstances, Lewis undoubtedly would have been working in higher circles, possibly even ‘diplomatic.’

We didn’t discuss Lewis’ problems, knowing we could only expect official disapproval if the American Embassy should hear about it. We knew a young couple with the consular corps who wished to entertain the newly arrived US Ambassador in their home, as they had known him in a previous post. They had only one ‘girl’, who had little experience and who they felt was inadequate. They had dined with us on a previous occasion, and remembering Lewis’ exquisite serving abilities, they asked if they might “borrow” him for the occasion and invited us to come as well. Lewis was obviously pleased to do it but was careful not to show any emotion. He was taken over to their apartment early to help with the table and receive his instructions. We arrived an hour and a half later to be formally ushered into the room in his rather stiff but regal manner, one of cold official function that showed no sign of recognition. I am sure the host and hostess duly impressed Mr. Ambassador with their beautifully trained servant.

When we complimented him later on his performance, he told us with quiet dignity that he knew about such things. Then, matter of factly, he told us that he had once waited on an important English gentleman in an East African hotel. His name was Churchill. “Winston Churchill?” we asked. He nodded. We had no reason to believe that he would lie, for he would never have been aware of this man’s great importance had he not served him.

With his “spit and polish”, Lewis could have succeeded almost anywhere, but he had two strikes against him. Not only was his passbook useless, he was living in South Africa as an illegal immigrant. We discovered this soon after he came to us. We kept searching for some legal way of keeping him.

Hopefully, we took him to a lawyer friend, an honest man and sympathetic to the complex problems of the African and his cause. Though he sympathized with Lewis’ case, he knew the law and was giving us legal advice. He advised us to get rid of this “boy,” as we would have nothing but trouble with the government should they find out. We would also be liable to heavy fines, as we knew, or perhaps even worse consequences, which we hadn’t allowed ourselves to think of.

Certainly, being foreigners did not make us immune to the laws of the land. Upon returning home that day, we had a firm talk with Lewis, saying that though we would very much like to keep him, we simply could not afford to do so. Lewis insisted that he could look out for himself, that he would be no problem to us. He pleaded with us to let him stay, saying he had no place to go. “They will never find me, Madam.” He promised to disappear if the police came. I wasn’t at all sure how he proposed to do that, but I finally agreed with Bob to allow him to stay only until he was able to find work elsewhere. It was shortly after this that we realized that we couldn’t get along without him. He knew this all the time, of course. We kept Lewis for two years, until we moved away from South Africa.

We learned something of Lewis’ background in the weeks that followed. He had a wife and family in Mozambique to whom he regularly sent money and other items by friends and relatives living under more or less the same circumstances as he, but who were returning home. Upon checking his personal references, we learned of his time spent in Johannesburg before coming to us. His most recent employer, for whom he had worked seven years, died, leaving a widow who now lived with her son and daughter-in-law in an apartment. They praised Lewis highly, saying that he had been a loyal, honest, and hard-working servant. They had to let him go when the old man died, not being able to keep him in an apartment building. They had been unable to place him in another home because he didn’t have a valid pass. Lewis told us that he had gone home to PEA every two or three years, going by back roads and paths frequented by laborers of Central and North Africa going to and from South Africa. Lewis’ home was a fishing village in northern Mozambique. Several times after our first visit to the lawyer, we tried to find a legal way of hiring Lewis, but it was hopeless. We finally realized we could do nothing for him except protect him.

Lewis had been with us six weeks when the police came! A few days before I had fired a new maid for drunkenness. Probably in retaliation for this, she reported to the police that we had an illegal houseboy. Of course, when questioned, I had to admit to the police that we had had a boy named Lewis working for us but that I didn’t know where he was, hoping against hope that this was the truth. It was! Lewis must have gone out the back door as the police entered the front. He had taken time to remove his clothing from his room. I hadn’t anticipated that he would do this, but it certainly helped my story when they searched it and found nothing. He had indeed fled. I insisted with honesty that I didn’t know where he was now. He had disappeared! Getting off with a stern warning that it was against the law and dangerous to hire a native not having a pass, I watched them depart. When all was quiet, I was relieved that Lewis had had the wisdom to leave. I hoped he would go to his remote fishing village and that Goli would be only a memory to him as he returned to the simple life of his homeland. I was wrong. He came back three days later. We reprimanded him for returning, but the house badly needed his attention, and we found it easy to forgive him.

Three times more he hid like a criminal, and I lied like one. Luckily, two times the police were not fluent in English, as I couldn’t speak or understand a word in Afrikaans (similar to Dutch), I found it easy to stand up under their questioning. Each time though, I was given a stern lecture on the dangerous native. We were in a difficult position, and we had no one to blame but ourselves. We were not anxious to break the law, especially since we were American citizens. South Africa is a beautiful, diverse country, with more than its share of problems. We had many South African friends, few who were in sympathy with the present government but who did feel that some of the laws were justified. Certainly, the control of the influx of Africans from the north was necessary, as the influx of Mexicans is necessarily controlled in the United States. Yet, if Lewis were caught, he would be taken to work on a forced labor farm until he earned enough money for his transportation back to Mozambique. I shuddered at the rumors of forced labor camps, hoping the stories were not true.

Why did Lewis take the risk of staying? Because in Mozambique he couldn’t make a decent living. Living standards of the Africans are very low there. The wage scale is almost nil. Though he had few civil rights in South Africa, the standard of living and the wage scale were the best in most of Africa. Despite criticism, South Africa has done much to give better housing to the African and to educate the masses, biased as it may be. In Mozambique, punishment is medieval. For instance, an African’s hand can be cut off for stealing, and it is said that many an African disappears after committing a more serious crime, though there is no capital punishment. Some say there is an island in the Indian Ocean where criminals are taken and from which they never return, nor are heard from again. Knowing the predicament, he had put us in, he tried especially hard to please. There was little doubt that Lewis appreciated the risk we were taking for him.

Lewis prepared a beautiful table. He was in a state of constant frustration due to our lack of sufficient silver and crystal, insisting on such items as fish knives and wine glasses which most Americans don’t use except for very formal occasions. He took over the flower arrangements and table centerpieces, and the few times I decided to do them myself, he was obviously hurt and brooded, so that I finally relinquished the right to do them. I found that he did them much better than I did anyway. He was very artistic and was fully aware of his unusual talent. One day I found him in the flower room, a small room with a sink and counter adjacent to the kitchen, making what looked to be a mud pie. He gave me a rather glowering look, which I took to mean, “This is my department.” We were planning a dinner party for two important visitors from my husband’s New York office. Lewis knew that I had been in a mild state of panic over their visit and had been preparing the menu for some days. Finally, when he announced dinner that night, there was the most beautifully laid table we had had yet. The centerpiece was an intricate arrangement of dwarf zinnias, marigolds and African daisies from our garden, the foundation of which only I knew to be a mud pie on an aluminum tray. Another time, Easter morning, we left for church, having first told Lewis that we were having guests for Sunday dinner. When we returned, there on the table was another exquisite arrangement, also in mud, of red and white verbena arranged in the shape of a cross, the white cross on a red background. I expressed my appreciation and surprise that he knew about Easter, his being Moslem. He said, “Oh, I know about such things, Madam.” There seemed to be little about which Lewis didn’t know.

He had little to do with the other servants after working hours but stayed to himself. Each servant had his or her own room, and his life was his own when the work was done. Where we sometimes had to speak to the others about having too many visitors or being too noisy, there was never a problem with Lewis.

He had been with us a little over a year when he asked one day if he could unfold something on the lawn that was too large to undo in his room. He wanted to pack it up and send home to Mozambique to his family by a cousin who was leaving the next day. Half an hour later Bob called me to come and see what Lewis had made. I was amazed at what I saw! Covering half our lawn was a beautiful handmade fish net. It must have been at least twenty feet wide and sixty feet long. It had been made entirely by hand and exclusively out of string. My thoughts raced back to the many times Lewis had asked me for bits and pieces of string left from boxes and parcels. Lewis had spent almost every evening for a year sitting in his room working on this enormous net, a real masterpiece. Lewis was most humble about it but very pleased that we liked it.

As far as being a houseboy, Lewis knew his job perfectly and did it well! He took pride in his work. Except for setting the table, serving, polishing silver, and doing the flowers, Lewis worked in other areas of the house other than the kitchen wing. That was the cook’s domain. We had hired a cook at Lewis’ insistence, as he said we needed someone fulltime in the kitchen. He also stressed that with a cook, Grace could focus on her job as nanny and house girl. However, once when Anna the cook was sick and it was Grace’s night off, I asked him to help me clean the shrimp for supper. They came with all their parts, eyes, feelers, shells, etc. I was a little afraid he would feel insulted, but he quite happily joined me in the messy job. Much to my surprise, he then asked if he could prepare shrimp in the Portuguese East African style of his own home. I enthusiastically agreed, guessing that he must be hungry for Portuguese cooking or that we wanted to try it, too. Though he insisted that he had made it mild for our sakes, it was excruciatingly ‘quente’ (HOT!). He laughed as he refilled our water glasses several ties, promising to make it milder next time. Though my mouth burned pleasantly for some time, it was delicious. Whenever we hungered for shrimp after that, Lewis was the chef and Anna occupied herself elsewhere. She and Lewis were good friends, and this amused her.

Lewis was extremely thoughtful of my parents during their South African visit. Africans have much respect for the elderly and care patiently and tenderly for their own aged. He was particularly careful not to disturb them, yet he was attentive. On his own initiative, he kept fresh flowers in their room and waited dotingly upon the “old madam”, as he called my mother. He had a soft spot for her because she, too, lied for him once when the police rudely pushed their way past my mother in the front hall. After asking for me or my husband and both of us out, she was bombarded with questions. When the police insisted that a boy named Lewis was there, my 5’ 2” seventy-four-year-old mother stepped out of character and emphatically denied that she had ever seen or heard of a boy named Lewis. They searched the house despite her protests, finally leaving when they found no boy other than Jack, whose pass fortunately was in good order. The other servants always lied with impassive, blank faces that showed they knew nothing about Lewis. They knew that all too easily they might be in a similar position one day. After the police left, Lewis came out of hiding; he had been behind the old sliding panel in the den. Lewis, with every reason, appreciated her efforts for his safety, though she was practically in a state of nervous collapse when I returned home.

Lewis had only one fault as a servant. He drank. This only happened about five times and usually when Bob was away. It was always on native liquor, no doubt brewed in our back alley and strictly illegal. Had it been anyone else, we would have fired him immediately. If anyone had reason to drink, Lewis did, and we tolerated it. In his inebriated state, he was still respectful, though he did threaten to kill our two maid servants, Grace and Anna, several times. Luckily, he never actually tried to accomplish this, and I doubt that he ever really meant to, but they believed him, and I had my hands full until his troubles were drowned. My husband, of course, scolded him severely on these occasions, and Lewis was always completely humbled and sorry afterwards, working harder than ever to make up for his wayward ways.

Lewis admired my husband and wanted to do as much as possible for him. He was his self-appointed valet. Lewis allowed no one else to press the “doctor’s suits”, iron his shirts, polish his shoes, etc. He kept his den in perfect order, regularly dusting the many books, carefully polishing the African carvings and other artifacts collected over the years. The two seemed to have a mutual respect for each other. When Bob was away on one of his extended trips of a month to six weeks, Lewis insisted on sleeping in the kitchen with his spear, as my guard.

I never had to tell Lewis to polish the silver or brass, to clean the windows or to do the floors. These always seemed to get done at the proper time. There was order in Lewis’ life. He daily prepared fires in the seven fireplaces during the cold winter months in our drafty old mansion without having to be told. He did this morning, afternoon, and evening - quite a job! He never left a mess, nor got a smudge on his clean white clothes. Much to my annoyance, he used to awaken me every morning before 6 a.m. raking out the coals from the downstairs fireplace.

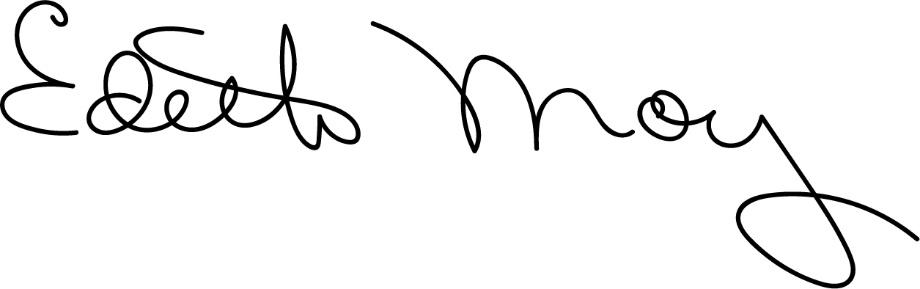

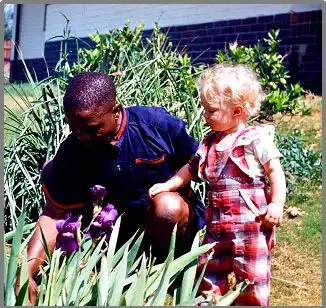

During the day, I would sometimes hear him muttering impatiently to himself about the mess the older children, Jan and Peggy, made but Lewis was never impatient with our youngest, Walter. He took Walter as his own charge, despite the fact that he had a nanny, Grace. It was almost as though he thought Walter needed masculine protection from all the females. He could quiet him if he cried, fix his toys if they broke, find them if they were lost, feed him if no one else could, and whisk him away from the table if he became unbearable. Walter returned this affection by learning to say “oois” before he called anyone else by name.

When it came time for us to leave South Africa, our servants were easy to place. Good, reliable servants were hard to come by. But we could not get a job for Lewis. By 1960 laws were even more severe than when we had hired him. No one dared take the risk that we had taken those two years. Lewis understood this. I phoned his ex-employer’s family, asking them to please help, and they sincerely promised to try. When we left Windy Gates, we shook hands. No longer in his white suit, though we gave him all his old uniforms to keep. He looked somewhat smaller even a bit like the “boy” who had first appeared at our kitchen door two years earlier with hat in hand. Noting our concern, he said, “Don’t worry about me, Doctor. I know how to get along. Goodbye, Madam.” Our other servants went to the airport to see us off. He couldn’t, of course. With no pass, he would have been picked up. He had to stay in the background, the shadows, like a criminal. Yet, he was so honest, I would have trusted him with the Hope Diamond. I imagine he is still watching, waiting in the shadows, slightly arrogant and proud, but taking care. He knew his worth. It was like a protective shell against the white world. Perhaps it was worth risking his freedom to stay in South Africa to prove his worth.

Every Christmas I hear from Anna and Grace about their work, and they sometimes send news of Lewis and Jack. They write that they miss us and the children. In Anna’s last letter, she wrote that Lewis had a good job working at a new boarding house in the Parktown area very near our old mansion. I wrote a letter to him, but he never answered. He was too independent. He wanted no ties. He was paid well for his services; now we were gone. Another year. Another family. He couldn’t afford to look back. It had to be like that with him. But I hope that sometimes when he is sitting alone in his room, somewhere in Johannesburg, twisting bits of string and working it into another fish net, that he remembers the American family he served so well. They certainly remember him.

Postscript

A letter arrived shortly after this story was completed. It read:

Dear Sir and Madam,

First of all, I must ask for an apology for my long silence, in spite of all the Christmas cards you sent me which all reached me safely.

Now Lewis was arrested for having no reference book and was deported to his home.

Passing my hearty greetings to all your children.

Yours truly,

Anna Chalatse