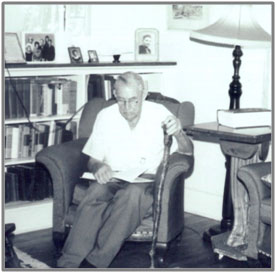

Mr. Babcock sat in his old wooden rocking chair, his rubber-tipped can held firmly in his gnarled hand, rhythmically tapping the floor as the chair rocked forward and back again. It was a sound which could be annoying if there were anyone to hear it, but he was unaware of any sound at all. Mr. Babcock was almost deaf, and he could hear almost nothing when his hearing aid was turned off. More and more he shut out the world and became lost in his own thoughts. Few people bothered to attempt to talk to him anymore, and when they did, he didn’t understand, and he knew he had misunderstood them when they looked at him oddly. He had given the wrong reply. As many who are hard-of-hearing, he sought refuge in his books. Always an avid reader, these were his only friends these lonely days.

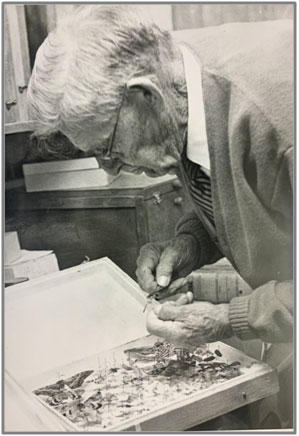

When one reaches the age of eighty-seven, there are few friends left! His library shelves were lined with books, all of which he had read. He had a habit of underscoring points he wished to remember, and if it was something he especially wanted to remember, he put in a little squiggle, which looked like a hand pointing to the line. His library contained everything but modern fiction; biographies, science (biology, entomology, geology, botany), adventure, travel, history and geography. There was a set of bound copies of the classics, well worn, probably left from his college days. He had no use for people who didn’t read, and only with the urging of his daughter, did he finally agree to buy a television to be brought into the house, for the use of his housekeeper who refused to work there without it. But he seldom watched it. He did agree to watch the NASA landing on the moon in 1969. It was on his birthday. This gentleman had been born into a world when horse and buggy and steam engines pulling trains were the only means of transportation. Though his hearing was nearly gone, and his eyesight dimming, and he was nearly crippled with arthritis, his mind was still good. He could locate any paper in his files, any book on any subject, and usually any reference he needed. His books were filed according to topic as in a library. Journals were bound chronologically, waiting to be used to be referred to when needed.

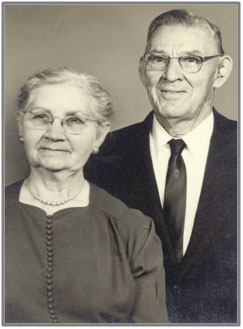

His wife had died three years earlier which left him devastated. But he was practical enough to face the reality of death, and though the loss of his beloved helpmate and companion left him essentially alone, he never lost his zest for life. He had a lifetime of experiences to reflect upon, but no one to share them with. He had a brain filled with knowledge of years of study and research, but no place to use it anymore. Some people in the community who had known him thought of him as an eccentric, but a kindly old man. Neighborhood children loved him for they could bring him their captured insects, snakes and rocks to be identified. And he could share stories with them, but children don’t have much time to talk to old men either, now that television took their spare time. And old men cannot go seeking youngsters. Winters were long and cold and dark. Mr. Babcock withdrew more and more from the world. His children lived in far-off places and though they came to visit with regularity, they didn’t come often enough, to his way of thinking. He had tried to get Edith to come back home and live. She was divorced with four children. They could be such company to each other, he and she. They had always been close. She was his baby. But she had explained to him that she had her house in the city and jobs paid better there. What could she do in this little hometown of hers? Be a clerk? Work in a bank? No, she told him. She had to think of her future and her children’s futures. She, in turn, begged him to come live with her, but he hated the city, and most of all, he hated being away from the home he had lived in for over fifty years. No, he would never leave, he said firmly.

He had been sent to this isolated part of Texas by the Department of Agriculture, at an experiment station in the area to help sheep and goat ranchers cope with the many pests destroying their animals. He grew to love the arid west, and no one could force him to leave now. His beloved Edith Stella was buried in the beautiful cemetery north of town in a plot shaded by live oak trees which they had chosen years before. When he bought her tombstone, he had had his part engraved with his name and birthdate, also with a space for the date of his death. He was a practical man, and though he hated the thought of death, he was not afraid of it. Nor was he looking forward to it, as many do, or say they do, in old age. He wished to live to be 100, he often said.

Edith saw the familiar light ahead. The streetlight on the corner of the block where her home stood, the house she had grown up in. The familiar old giant pecan trees guarded the front gate. She pulled up in front. As she stepped out of the car, she smelled the familiar West Texas air, so fresh this afternoon. There must have been a shower, she thought. She wondered if he had unlocked the front door for her, or if she would have to go around back. He could never hear the doorbell or a knock. She wondered how many visitors he had missed because of his poor hearing. Of course, there had been Mrs. Gray these last three months to answer it, but now she was going, which brought Edith to the present and the reason she had made the hurried trip to get him.

Inside Mr. Babcock was still rocking in the late afternoon sun that was forcing its way into the west window. He was mulling thoughts around in his head and how he was going to handle Edith when she came. He had already scratched out an advertisement to put in the local paper for a housekeeper. He didn’t really like Mrs. Gray too much but tolerated her because he knew if he didn’t have someone there to take care of him, his children wouldn’t let him stay in his home.

He would get Edith to take him down to the newspaper office as soon as she arrived. If he could only convince Edith that he was able to cook for himself. He didn’t have to have anybody. Well, maybe a cleaning woman once a week would help. She could change the bed and do his laundry. He could send her to do the grocery shopping, too. “Darn Edith!” he thought, “She can’t tell me what to do. I won’t go. I won’t go back with her. There’s nothing to do at her house.” He rocked faster when he thought about how life would be there. Of course, he loved his grandchildren, especially his grandson, but he was away all day too, and had his studies at night. And there was always that infernal television… “Ought to be outlawed,” he mumbled to himself.

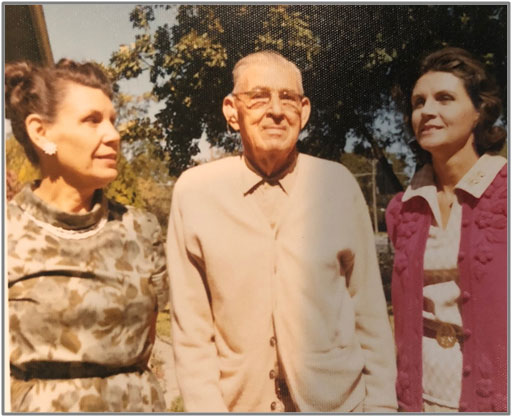

He was startled by a hug from the back and a kiss. “Edith May,” he shouted, “How did you get in here without me hearing you?” He quickly turned up his hearing aid so he could hear her. She was beautiful to his eyes, like her dear Mother, same eyes, same hair, same lovely smile. His baby.

“Daddy, you look so thin! Haven’t you been eating?” she demanded.

“Of course, I have. I just miss your mother’s cooking. Mrs. Gray was not such a good cook. She was always cooking special things for her diet, and I just ate whatever she fixed.” “Did you bring the children?” he asked hopefully.

“No, they’re in school and it is too near exam time to let any of them miss a day of school now,” she answered. “But they’re looking forward to you! And the baby has moved in with the big girls, so you have her room just waiting for you. They’ve even decorated it with their paintings, and we put the big old rocker you gave us in there so you can read there when things get noisy,” she said eagerly. She looked at him, and he looked troubled. As if afraid he would start protesting, she hurriedly continued, “And Jan has baked you a rhubarb pie, your favorite! We’ll warm it up in the oven for your first meal. Now what are you going to have for supper? Let’s see, didn’t Mrs. Gray leave anything for tonight? When did she leave?”

“Well, she left this morning,” he answered. “She didn’t say anything about food for tonight. I don’t think she had time to fix anything. I fixed my own lunch, some leftover tuna fish I found in the fridge.”

Edith put her things into her old room. The same bed she had slept in for seventeen years before she left for college that many years ago. “Well, I thought that might happen, so I stopped and bought a box of fried chicken just in case. So, let me get some salad together, and we’ll have a feast in a few minutes.”

“Edith,” he called, “before we do, could you drive me down to the newspaper office. I have something I want to do.” She turned around, knowingly. “Now Daddy, what are you up to?”

“Well, I want to put that ad in for the housekeeper. Edith, I can’t live in the city. Webs will grow between my toes. I hate that damp place, mildew, mosquitoes, pine trees. This is my home now. I’m happy here with my memories and my books.”

“Now, Daddy. I know you don’t want to live there,” Edith implored. “I plan to put an ad in the papers, but not just here but in San Angelo, Dallas, Fort Worth and even Houston. It’s not easy to find a good person, and we are not leaving you with just anybody.”

She was looking through the cupboards for the salad seasoning when a cockroach crawled past her and she jumped. She noticed the cupboards were dirty and when she opened the refrigerator, it was dirty and almost bare. Other things came into focus. What had happened around here? Dirty dishtowels, dishes stacked any which way, a couple of frozen dinners in the freezer. She walked out to the utility room to get a broom to clean up the mess by the waste basket and there must have been five sets of sheets there and a bundle of dirty towels. “Daddy”, she called, “What’s been going on around here. Didn’t Mrs. Gray do any work? The place is a mess.”

“Well, I thought you’d be upset when you saw it, but I didn’t want to say anything to her for fear she’d leave. But she left anyway. Mrs. Gray didn’t seem to like housekeeping or cooking for that matter. But she was a good woman. She didn’t smoke or drink and she drove me to the post office every day and took me to the cemetery. She always ate alone though, so I didn’t really get to talk to her very much. She liked to watch the television which I don’t like, as you know. But she wasn’t bad.”

Edith said, “But she was so nice when we interviewed her. I thought she was eager to work here and take care of you. No wonder you’re so thin. Did she ever visit with you or bake cakes or cook the things you like? Did she make up your bed and wash your clothes?”

Edith was exasperated and angry. Tears of frustration appeared which she quickly wiped away. Mr. Babcock sat helplessly in his rocking chair trying to defend Mrs. Gray, but he knew he couldn’t. He didn’t care who he had as long as he could stay home. He was sorry Edith had to find out the truth.

“Why didn’t you write me and tell me what was going on?” she insisted.

“Oh, Daddy, you can’t stay here. Look at this place! We have to get the exterminators out. She’s left so much dirt around. It’s filthy.” He watched her go off to inspect the rest of the house.

He knew now that Mrs. Gray didn’t want to wait for Edith to arrive because she feared she’d be mad. He was sorry she had decided to leave so suddenly, but he guessed she got bored in this small town with no one to talk to but him. All she did was watch the television though and a slight attempt at tidying up and putting skimpy meals on the table. He had been able to fill up on graham crackers or cereal when he didn’t feel satisfied. The family gave her shopping money for food and supplies, as well as a good salary.

When Edith came back into the room, she looked upset, but tried to be cheerful. “Well, let’s forget Mrs. Gray and get supper, o.k.?” She came over and ruffled his hair and gave him another hug and kiss. "It’s so good to see you again. It’s been three months. That’s just too long.”

She put some laundry in the machine, fearing there were no clean linens. After they finished the last of the fried chicken, she made up both beds with clean sheets, and hung up the dress she would wear tomorrow. She was still furious with the knowledge that Mrs. Gray had been making a cool $450 a month doing practically nothing. And, she’d had good references, too. “Real good person, former schoolteacher, no children, a widow, fine Christian woman” Ha! She picked up the phone to call home. The children said they were fine and to please come home soon. “I’ll be home with Granddaddy on Sunday,” she said. “Have his room ready and Peggy, please put a fresh vase of flowers on the dresser, will you? Thanks, I love you all.”

Then she called her older brother, Kenneth, to tell him the bad news. What to do? He or Gertrude, her older sister, would know. They would hold a family conference soon to decide what to do with their poor Daddy. He wanted to stay home in his own house with his office, books, and his garden.

Note: During this time, after his wife’s death in 1968 to his own in late 1973, there were four different housekeepers. He suffered a stroke and spent six months in a nursing home. He recovered enough to lead a fairly normal life. He lost his eyesight to cataracts and was considered too ‘old’ for cataract surgery in those days. His family doctor of many years recommended a superb housekeeper and companion who was with him until he died of a massive stroke. She was an angel and made his life tolerable. The three siblings took turns visiting him for his remaining years in his house which is all he wanted to do, live out his remaining years “at home”.