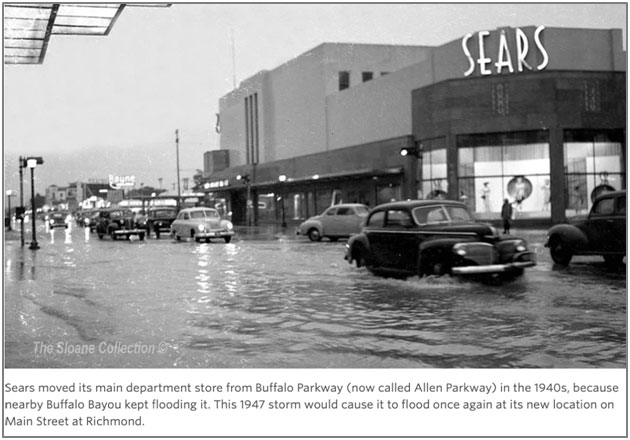

The year was 1949. It was my husband’s third year of medical school, really ‘our’ third year, for I fully expected to get my ‘Consort of Medicine’ at the end of our four-year stint. We had married the week before he entered Baylor College of Medicine in August 1946. Anatomy classes were in the old Sears Roebuck warehouse that first year, while the new building, the first to rise in Texas Medical Center, was completed. Times were hard after the War. Few students had any money, but nearly all had the G.I. Bill, and we all struggled along together. It was all love and roses. It didn’t matter that we were poor, for everyone else was, too.

We were lucky, for we had no children and I could work. My salary supplemented the G.I. Bill. We all lived in tiny apartments and either furnished them with leftovers from our families or picked up used furniture from wherever we could find it, throwing in an orange crate or two when needed. Our friends with children really struggled, and we often visited them in the new housing development for the poor, which is now called Allen Parkway Housing. Hardly anybody had a car, unless they were fortunate enough to have parents who could donate one. We were not that fortunate. This was unlike today’s youth in that few parents gave their children cars after graduation. My husband did enter marriage with a bicycle, the old-fashioned kind, now called a ‘no speed’. That and the city bus took us wherever we wished to go. It took him two miles to Baylor and occasionally he detoured and took me to my bus stop. Rain or shine, it always worked!

For two and a half years we got along with the bike and the bus. We had reliable transportation. I had gone through three jobs. The first paid $100 a month as a copywriter for Levy’s which was Houston’s best department store just before Foley’s was born. I got a $25 per week increase with an advertising agency plus a bonus every time I posed for one of our advertisements such as one for mosquito spray, a wheelbarrow ‘women could push’, ‘interviewing’ for an entrance to Massey Business College. I don’t think there were such things as model agencies in those days, and they paid me about $15 per picture.

All this added to the coffers and we finally decided we should save to buy a car. Bob earned money on weekends inspecting meat in a meat plant and this helped, for he also got meat at a discount. Then I heard about a great job at Humble Oil Company that paid $200 a month. I applied and got it. We were in business!

We had heard about a new small car on the market. It was a Crosley. We went to the dealership and looked it over. The one on display was a yellow station wagon. It was very small, but after two and a half years on a bicycle, it might as well have been a Cadillac. We took it for a test drive and felt like we were riding along about ten inches above the pavement, which we were! The seats were on the floor and our legs stretched out in front of us. But it was amazingly comfortable. What wouldn’t be after the bicycle? There used to be a car on the market called a Baby Austin. It was smaller than that, in height, but in length, it had a nice roomy area behind the back seat. We could lay down the seat, as in today’s compact cars and have room for suitcases, dogs, bedrolls, or most anything.

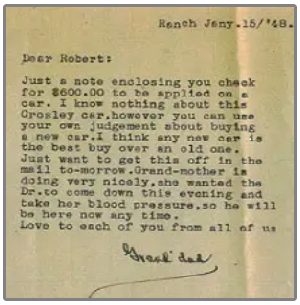

with enclosed check toward car purchase.

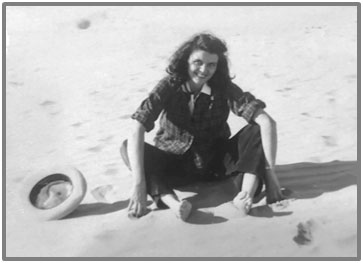

I don’t remember the exact measurements but would guess it was about four feet high and six feet long. The wheels were normal looking but scaled down accordingly. We bought it for about $800. As soon as he had a free weekend, we planned a trip. We took it to Galveston for an overnight camping trip on the beach. Soon we had our camp set up, our wooden and canvas cots set up on the sand. We built a campfire and roasted hot dogs and marshmallows. The surf sang us to sleep under the stars. What bliss!

We hadn’t camped out since medical school started, or for that matter, in our entire lives except at Girl and Boy Scout camps. The car had given us this new freedom. We knew if it rained, we could get in the back of the station wagon, though it would be a bit cramped we admitted. We slept well, for we were both exhausted from an unusually strenuous week, plus the energy spent in getting ready for this trip.

During the night we had been faintly aware of a few cars driving in, and we heard people setting up camp like ourselves. We didn’t let it bother us and slept peacefully on. The sun rose early over the beach and as the light brought things into view, I looked around. We were nearly surrounded by cars and people, sleeping all over the sand, in cars, on cots. I sat up with a start. I looked more closely at the forms and gasped. I woke Bob. “Bob,” I whispered, “Wake up. Quickly! Don’t make a sound. We’ve got to get out of here.” He sat up and looked around at the scene surrounding us and leapt up. We quietly folded up our cots and put our bedding in the back of the station wagon. We jumped in the car, started the engine, and sped away for Houston. “What happened! Why did they all come? Where did they come from?” We were puzzled. Then we remembered! It was June 19th or Juneteenth, Emancipation Day, and they had come to Galveston on ‘their’ holiday. We were the only white people on the beach. In 1949 segregation was still law. We had been scared out of our wits. In our eagerness to get away from Houston, we didn’t even think of such a thing, and the day would have gone unnoticed in our lives, but for the night on the beach in Galveston. Martin Luther King and Selma, Alabama were yet to come.

Southerners considered themselves tolerant, broad minded and understanding. Some even dared to be liberal. I knew a professor who awoke to find a cross burning in his yard because he dared have a Negro visit him in his home. I had grown up in far West Texas where our only problem was a ‘Mexican problem’ and until my marriage and move to Houston, I had hardly ever been around Negroes. I accepted their riding on the back seat of the bus and drinking out of ‘colored’ water fountains, but I would never call them ‘Nigger’ and considered anyone who did to be ill bred. My husband was less tolerant than I, because he had been raised on Civil War stories and had been told numerous times that his own father was kept home from school when the history class studied about the Civil War and Abraham Lincoln. I thought that was incredible! My family came from the ‘North’, as far as the Civil War was concerned, even though ‘north’ was Colorado. The Crosley brought the racial issue in focus. We were scared! Scared out of our wits! It made a good story for some time.

We kept driving the little Crosley until it floated away one too many times in West University during a Houston flood. But it got us through medical school. Soon after his graduation we were able to buy a used Chevrolet, but nothing matched the sheer joy of owning our first set of four wheels with a tin can body which was just about what the car amounted to. Even so, I think if the Crosley had been invented today, it might have become an instant success. It averaged about fifty miles to the gallon and took us all over the State of Texas on vacations. But no trip was as memorable as that first trip of sixty miles to Galveston, Texas. Now, when I look back at pictures of our little car, I marvel that we could both sit in it at once, much less drive it for two more years. I marvel even more that I lived to tell about our first car, the little yellow Crosley.